The Duplex Drive Tanks of Omaha Beach, Part (e) Success at the Dog Beaches

This installment follows the DD tanks of the 743rd Tank Battalion, which were scheduled to land on the western half of Omaha Beach. These tanks belonged to Company B (CPT Charles W. Ehmke) and Company C (CPT Ned S. Elder) and were embarked in eight LCTs under the command of Lt.(jg) Dean Rockwell, USNR. In contrast to the debacle on the eastern half of Omaha Beach, the popular story of the landing of the 743rd’s tanks was one of complete success, due primarily to the excellent judgement and resolve of Lt.(jg) Rockwell - and maybe CPT Elder, too, depending on which story you read.

This installment digs into the facts behind that popular story, relying on Rockwell’s little known 1990 oral history which revealed a key element of the popular story was not entirely true. It also includes a never-before-published photo taken of a knocked out DD tank on Dog White beach sector.

The Price of a Beachhead. Knocked out Duplex Drive tank of the 743rd Tank Battalion and casualties from the 29th Infantry Division, astride the seawall near the boundary of Dog Green and Dog White. This never-before-published photo was taken by Tech/3 Burton Hartman, Detachment Q, 165th Signal Photo Company, and is used here with the permission of his son, Barry. It’s believed to have been taken early D+2. (Copyright protected, use without the permission of Barry Harman is forbidden)

Introduction

In the previous installment (The Duplex Drive Tanks of Omaha Beach, Part (d) The Debacle Off Easy Red and Fox Green) we followed the story of the DD tanks of Army Captains (CPT) James Thornton and Charles Young, and the Landing Craft (Tanks) (LCTs) of Lieutenant (junior grade) (Lt.(jg)) Barry that carried them to the eastern half Omaha Beach. That account focused on the series of bad decisions, poor planning and mistakes in execution that culminated in 27 of the 32 DD tanks sinking before reaching the beach. This installment follows the DD tanks of the 743rd Tank Battalion, which were scheduled to land on the western half of Omaha Beach. These tanks belonged to Company B (CPT Charles W. Ehmke) and Company C (CPT Ned S. Elder) and were embarked in eight LCTs under the command of Lt.(jg) Dean Rockwell, USNR.

In contrast to the debacle on the eastern half of Omaha Beach, the popular story of the landing of the 743rd’s tanks was one of complete success, due primarily to the excellent judgement and resolve of Lt.(jg) Rockwell - and maybe CPT Elder, too, depending on which story you read.[1] Those versions of events might possibly have been influenced by the fact that the only source for them was Rockwell himself. Neither of the Army company commanders survived long enough to bear witness to what happened that day. Captain Ehmke was killed soon after his treads met sand on D-Day. Captain Elder was killed in action on 14 July (coincidently, the same day Rockwell submitted his report on the landings). The confusion resulting from the intense combat and casualties during the landings resulted in the battalion’s documentation of the day being rather incomplete.

So, the story of the battalion’s landing has been almost completely dominated by Rockwell’s contemporary official report and Read Admiral (RADM) Hall’s self-serving endorsement letter. That is, until a new narrative appeared in the early 1990s which called a significant aspect of the ‘official’ account into question. Unfortunately, this new narrative had extremely limited exposure, which is a shame, since it, too, came from the pen of the former Lt.(jg) Dean Rockwell.

Sortie and Crossing

As discussed in the previous installment, the initial 4 June sortie had been halted and turned around due to an unfavorable weather forecast for 5 June, the original invasion date. The false start helped the DD/LCT force as it permitted hasty repairs to some ramp gear that had been damaged in the initial sortie, as well as replacing one LCT engine.

The false start had also demonstrated to Rockwell that the revised sailing formation had placed Lt.(jg) Barry in a position from which it was impossible to control the eight LCTs in his division.[2] Less than 3 hours prior to the second sortie, Rockwell switched the officers in charge (OICs) of two LCTs, placing Barry at the lead of his force.[3] It was good decision, but made far too late, and was to add to the confusion in that division on D-Day.

Rockwell was spared that confusion within his own division. Unlike Barry (who was assigned as the OIC of LCT-537) Rockwell was the commander of an LCT group and was not the OIC of a vessel. To cope with the new sailing formation, he could shift his flag from craft to craft without disrupting the internal chain of command of his LCTs

During the crossing of the English Channel, Rockwell exercised command over all 16 of the DD/LCTs headed for Omaha Beach, to include Barry’s division. During this second sortie, the DD/LCTs encountered additional confusion caused by the Utah Beach convoys that hadn’t had time to return to their ports of origin and had taken shelter in Weymouth Bay. It was chaotic, to put it mildly. When dawn came, the mass of shipping began to try to shake itself out into some semblance of order. Due to a shortage of minesweeping flotillas and time in which they could operate, the convoy lanes were narrow and the convoys themselves became intermixed and partially disrupted by smaller towed craft that had broken free of their tows. Amid this mess, Rockwell realized he’d lost one LCT. After searching for it for most of the morning, he found his lost LCT-713 sailing in a nearby convoy headed for Utah beach, and he ushered it back into formation. Perhaps it was no surprise. LCT-713 was one of the last craft built and one of the last craft to join the Omaha Beach LCT flotillas; craft and crew were as green as they came. Despite the challenges of heavy weather in the Channel and confused traffic in the convoy lanes, the multitude of ships and craft managed to arrive at the Transport Area anchorage off the Omaha Assault Area, in confused and straggling formations, but or more or less on time.

Figure 1. The D-Day Convoy Routes. This chart shows how convoys from all of the invasion points converged at Point Z (ZED) near the Isle of Wight before turning towards the coast of France. Although necessary due to the short time allotted minesweeping, the narrowness of the lanes resulted in jammed and confused traffic.

From Point K to the 6,000 Yard Line

On each flank of the Transport Area (23,000 yards off Omaha Beach) there were rendezvous areas for LCTs; one for the LCTs of Assault Group O-1 and one for those of Assault Group O-2. However, as the DD/LCTs would be first wave, and as they had arrived late, Rockwell brought both his and Barry’s divisions directly to Point K (aka Point King), located at the western limit of the O-2 boat lanes. At that point Barry’s and Rockwell’s divisions were to separate, with Barry’s eight craft continuing eastward to Point K-L (King-Love) on the western flank of the O-1 boat lanes. (See chart).[4]

Point K was an important and busy location early on 6 June. Also due to rendezvous at Point K were: eight Landing Craft (Armored) (LCT(A)) carrying wading tanks and tank dozers; eight Landing Craft, Mechanized (LCM) carrying the gap assault teams for the O-2 beach sectors; three control craft; and 12 landing Craft, Support (Small) (LCS(S)).[5] In addition, two Landing Craft Infantry (LCI), carrying the deputy assault group commanders for O-1 and O-2 would be there to shepherd the first waves into position. Rockwell placed his arrival in the Transport Area at 0345 hours and proceeded to Point K, where, he stated, he was met by LCS(S)s “that were to lead us to the line of departure.”[6] This was not quite accurate.

Lt.(jg) Bucklew, the OIC of the 12 LCS(S)s told a different story. He reported he, too, arrived at Point K at about 0345 hours where he found the DD/LCTs, the LCT(A)s and the LCMs. However, none of his other 11 LCS(S)s had arrived, and the guide craft had already set off down the fire support lane. The LCS(S)s had not made the Channel crossing on their own bottoms, rather were ferried over on the decks of Landing Ships, Tank (LSTs) and attack transports. As these larger ships arrived, they hoisted out the LCS(S)s, who then set out individually or in groups of two or three to find Point K in the dark, with only Bucklew’s craft arriving on time. Neither of the deputy assault group commanders were to be seen.

Bucklew made the command decision to remain at Point K and look for his lost LCS(S)s, and Rockwell made the command decision to proceed down the fire support lane to try to catch up with the guide craft. Each of these turned out to be a correct decision. Bucklew soon located his missing craft and the fast LCS(S)s caught up with the lumbering LCTs, taking station in two columns flanking the DD/LCTs. Rockwell was able to maintain contact with the control craft as he followed them down the fire support channel.

When Rockwell turned right into the fire support channel at Point K to pursue the guide craft, his formation had changed from two columns of four LCTs each into a single column of eight LCTs. It was during this evolution that the break in Barry’s division occurred (as discussed in the previous installment), with LCT-537 and LCT-603 mistakenly following Rockwell down the wrong channel.

As the DD/LCTs proceeded down the lane, the craft went to general quarters and the chains holding the tanks securely to the decks were removed. The tank crews began inflating the skirts and the Navy crew wetted down the canvas skirts with pumps. Once the skirts were inflated, the tankers and sailors could only communicate by shouting over the high canvas sides; not only was radio silence still in effect, but the Navy and Army radios were equipped with crystals that did not permit operation on the same frequencies. With the engines of both the LCTs and tanks running, verbal communication between sailors and soldiers was difficult. Communications between craft had to rely on visual signals, and communications between tank units was impossible – at least until 0500 hours when the tankers were allowed to break radio silence.

Rockwell’s action report provided little detail for this portion of the operation. Fortunately, in the early 1990s, he was contacted by Stephen Ambrose and agreed to tape-record his D-Day experiences. (Ambrose did not conduct the interview, Rockwell simply recorded his story.) Although held in the Eisenhower Center at the University of New Orleans, Rockwell’s oral history has been largely overlooked. Patrick Ungashick located a transcript of this recording (along with a number of associated documents) while researching his book, A Day for Leadership: Business Insights for Today’s Executives and Teams from the D-Day Battle. This transcript provided a bit more in the way of minor details (to include the earlier anecdote about the wayward LCT-713).

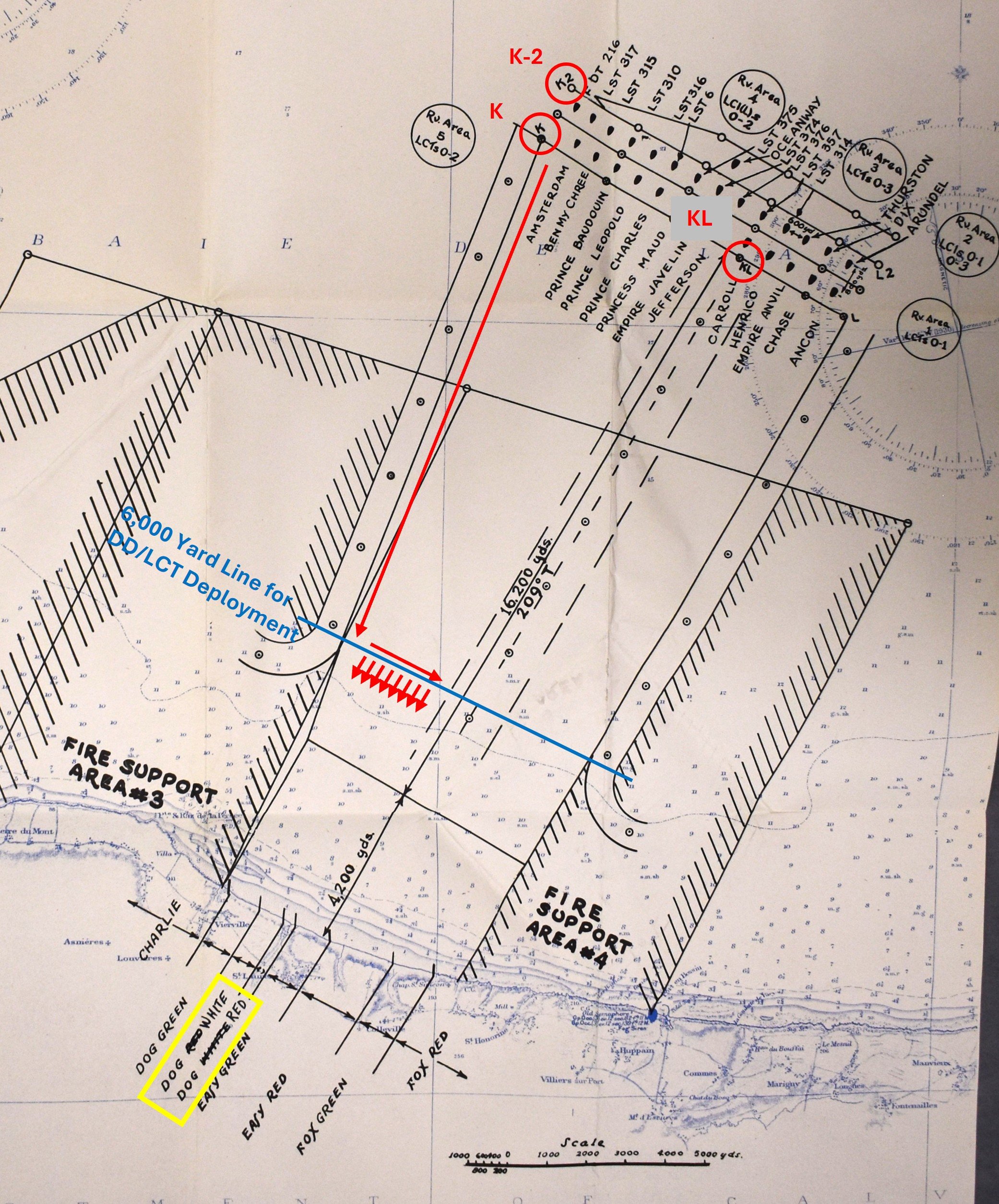

Figure 2. Omaha Beach and Surrounding Waters. This is a detail from the Omaha Assault Area Diagram which was contained in the Assault Group O-2/CTG 124.4 operation order. I’ve added colored notes and graphics to highlight items discussed in the article. The red arrows depict Rockwell’s DD/LCT division’s movements.

During the crossing of the Channel, the bombardment force, including two battleships and three cruisers, had overtaken the LCT convoy, and these ships were already anchored in their designated positions in the fire support channels. Ahead of Rockwell in his lane were the older American battleship USS Texas (BB-35) and the British light cruiser HMS Glasgow (pennant number C21). The Texas (Rockwell thought it was the battleship USS Arkansas, which was in the eastern fire support area) was a large ship and it was anchored across the narrow channel. Heavily ladened, shallow-draft, and buffeted by waves and wind, the DD/LCTs found it a challenge to avoid the Texas in the pre-dawn darkness. One of the LCTs lacked the seamanship to get by without scraping paint. The battleship was unfazed, but the LCT’s launching gear was damaged. Rockwell omitted this incident from his official report but included it in his oral history.[7] He didn’t identify the hit-and-run LCT, and none of the reports from his LCT OICs confessed to this accident. The report from LCT-713 (Ens White) did note that on beaching, his ramp extensions were damaged, so it may have been the culprit.[8]

Rockwell’s account makes no mention the Deputy Commander of Assault Group O-2. As you recall from the previous installment, CAPT Imlay, the Deputy Commander for O-1, was supposed to meet Barry’s DD/LCTs at Point K, but did not link up with them until near the 6,000 yard line. CAPT Wright, the Deputy Command for O-2, was also supposed to meet up with Rockwell’s division at Point K, but on arriving he decided it should stop at Point K-2 (a few hundred yards farther offshore) to direct the arriving craft. From there he proceeded to the LST anchorage area to supervise the unloading of the DUKWs. Wright’s normal job was Commander, LST Flotilla 12, and this probably accounted for why he allowed his focus to be diverted from the first waves. He did not proceed inshore to the beaches until 1100 hours. As a result, despite being the deputy assault group commander, he played no role in organizing and dispatching the early waves in the boat lanes.[9]

A senior officer who was present close inshore was CAPT L. S. Sabin, Commander, Gunfire Support Craft (CTG 124.8). Although he did not control Rockwell’s division during the approach to the beach, Sabin did command the convoy in which Rockwell’s DD/LCT group sailed to Point K, and he commanded the gunfire and rocket craft that were supporting Rockwell’s LCTs. He had also sailed down the same fire support channel as Rockwell, shepherding his gun and rocket craft into position just behind the DD/LCTs. As a result, Sabin paid close attention to the DD/LCTs that morning. While stationed close inshore before H-Hour, he reported:

“At least one LCT(DD) was observed to the westward, apparently having gone to Utah by mistake. He was headed back to Omaha, but it was obvious he could not make his position in time.”[10]

Rockwell did not mention this incident, either then or later, nor did any of his OICs admit to it. CAPT Sabin’s report was detailed and appears precise and accurate. It cannot be easily dismissed. Sabin’s observation is supported by Folkestad’s The View from the Turret. Folkestad cited an interview with Harry Hansen, then a lieutenant with the DD tanks of Co. C, 743rd Tank Battalion. Hansen stated during the Channel crossing, his LCT lost power and fell out of the convoy. Eventually the engines were restarted and the lone LCT wandered off course, eventually having to ask instructions from a French fishermen. This was probably the lost DD/LCT Sabin saw.[11] Hansen earned the Distinguished Service Cross, the Silver Star, the Bronze Star, and the French Croix de Guerre (with Palm).[12] And he ended the war as a captain. His account, too, must be taken seriously. Together, their accounts are fairly damaging to the credibility of Rockwell and his OICs, who portrayed the run into the beach as smooth and well organized, with not a hint of lost craft.

Despite these incidents, the column reached a point approximately 5-6000 yards offshore by 0515 hours (according to Rockwell’s official report) then turned left, proceeding parallel to the shore until the craft were opposite their target beaches at 0540 hours, at which time they turned right into line abreast formation facing the beach. There are minor differences when these maneuvers took place. Ensign Gilfert (LCT-590, last in the line of eight LCTs) reported the turns at 0530 hours and 0540 hours. Ensign Cook (LCT-588, fifth in line) reported the turn toward the beach as 0530 hours.

There are two versions of what happened next, and they differ in a key respect. Unfortunately, both versions come from Rockwell. We’ll first examine the version based on his 14 June action report and later consider the version from his oral history.

In his 14 July report on D-Day, Rockwell stated:

“At 0505 this command [referring to himself in the third person] contacted Captain Elder via tank radio and we were in perfect accord that the LCTs carrying the tanks of the 743rd battalion would not launch, but put the tanks directly on the designated beaches. Accordingly, all ships did a 90 degree flanking movement at 0540 and proceeded to the beach with the guide ship – LCT 535 – of this command touching down at 0629. The others all touched within two minutes.”

In addition to specifying the time of the launch-or-land discussion (0505 hours), Rockwell’s account sequenced the decision well before the command to turn right into line abreast to face the beach. Again, there is some disagreement on this timing. Ensign Gilfert (LCT-590) recorded that he got the word they would land the tanks at 0500 hours, and Ens Novotny (LCT-591) received the word at 0505 hours, supporting Rockwell’s time. Ensign Cook (LCT-588) said the Army captain informed him of the change “previous to” the flanking turn (which he placed at 0530 hours). But Ens Dinsmore (LCT-589) stated “It was 0530 when we decided the sea was too rough for the launching of the DD tanks.” Ensign Carey (LCT-586) did not state a time, but recorded, “. . . a short while later, orders came across the Army radio to form a line abreast and all ships land on the beach. This we did.” And Ens Pellegrini (commanding LCT-535, in which Rockwell rode) also gave no time for this decision, but placed it immediately before the turn into line abreast in his sequence of events. (The remaining two OICs, Ens White (LCT-713) and Ens Demao (LCT-587) did not mention when they received word of the change.)

Oddly enough, four of the six OICs (to include the OIC of the craft Rockwell was aboard) reported the decision being made, or their receipt of that decision, between the time the column turned left to parallel the beach, and the right flank turn into line abreast. This would place the decision close to the scheduled launch time for the DD tanks (0535 hours). Only two OICs supported Rockwell’s earlier time. The wording of Dinsmore’s report is especially noteworthy. He didn’t say he received word of the change. He stated: “It was 0530 when we decided the sea was too rough for the launching . . . “ [Emphasis added] That seems to imply the decision was made on his craft, which would also imply CPT Elder was aboard. We don’t know what craft Elder was on, and it’s risky to parse inexact timelines too closely, but this raises a possibility.

I question Rockwell’s assertion that he initiated contact with his Army counterpart. The tankers were authorized to break radio silence at 0500 hours, five minutes before Rockwell and Elder supposedly conversed via the tank radios. So it was likely these radios were used to convey a decision. But, as mentioned before, Rockwell had no physical access to those radios. Al he could do was leave the wheelhouse, walk forward in the well deck until he was next to the lead tank, and shout up the the platoon leader, with snippets of conversation relayed via that platoon leader. But that would rely on Elder first opening the net. It’s far more likely it was Elder who initiated the call when he opened the radio net and he who made contact with Rockwell. Which would imply Elder also raised the decision not to launch, as Dinsmore’s report seemed to say. This might seem to be a minor point, but given how we’ve seen Rockwell’s report was heavily spun to cast himself in a good light, it is important to clarify every point.

In fact, Rockwell was not consistent on the matter of who initiated the call. In his oral history, he gave a different version. In it he stated:

“. . . I was in communication by low power tank radio (even though all communications was forbidden prior to H-hour, the decision to launch or not to launch into the sea was absolutely critical to the success of the Invasion. We broke radio silence. What the hell, by now the Germans were aware what was about to happen) with a Captain Elder, of the 743rd tank battalion. We made the joint decision that it would be insane to launch . . . The next signal to all our craft and to the tank commanders that we would proceed to the beach, which we did. And when our landing craft drove up on the shore, the ramps were dropped and the tanks drove off, with their shrouds down, ready to provide coverage to the infantry units that were to come in behind them.”[13]

[As with all oral history and interview transcripts, the narrative reflects the natural speaking style of the individual, resulting in some odd wording and at times confusing syntax. I have not attempted to ‘clean up’ the text and have quoted them as they were transcribed.]

So, in this later version, Rockwell no longer claimed he initiated the call. This may seem a minor point, but it is important to remember that from the very start, Rockwell believed that the launch-or-land decision should be the sole responsibility of an Army officer. He clearly stated this in his 30 April 1944 report to RADM Hall on the DD tank and LCT training programs.[14] And he reiterated it in the days before the sortie, when he pressed for a single Army officer to decide for both battalions.

Yet he sang a much different tune after the successful landing of the 743rd’s DD tanks. Suddenly he was the man with the expert knowledge, common sense, authority, and responsibility and was acting to forestall disaster. Six years after his muted version in the 1992 oral history, he was back to playing the role of the decisive man at the critical moment. As he stated in a letter to Ambrose on 3 August 1998:

“I’m flattered by the credit you gave me for the part I played. Really, it was only a matter of a good judgement and a little knowledge of seamanship. The sea was too rough for the survival of the D.D. tanks. By tank radio the Army agreed with me. (I was going to take them to the beach even if the Army had disagreed.) As the senior Navy officer afloat directing this portion of the invasion, I had the authority and a responsibility to act.”[15]

This stands in stark contrast to his position before 6 June that he should have no role in such a decision. His later insistence on claiming to be the initiator of that decision—or co-equal in the decision—seems to be a rather crude case of rewriting history.

Figure 3. Deciphering Directions. Maneuver terms may be hard to visualize for those not familiar with military matters. This picture shows how Rockwell’s division of LCTs changed formations from Point K to the beach.

The Run into the Beach

After turning right into line abreast and facing the beach, the DD/LCTs could not immediately drive ahead. They had reached the 6,000 yard launch line early, early enough to allow the slow-swimming DD tanks to reach the shore at their scheduled H-10 minutes. But with the decision to land, adjustments had to be made. Since the LCTs were faster than the DD tanks, they had to slow their approach to avoid beaching too early, especially since in a landing scenario, they were supposed to beach 10 minutes later, alongside the LCT(A)s at H-Hour. Ideally, this would put 32 DD tanks, 16 standard wading tanks and 8 tank dozers on the beach almost simultaneously. So, Rockwell’s DD/LCTs initially ambled along, hoping the LCT(A)s of the next wave would catch up by H-Hour.

In Ambrose’s book D-Day, June 6, 1944: The Climactic Battle of World War II, the author’s dramatic narrative described Rockwell’s run to the beach in these terms:

“Further, the smoke obscured Rockwell’s landmarks. But a shift of the wind rolled back the smoke for a moment and Rockwell saw he was being set to the east by the tide. He changed course to starboard and increased speed; the other skippers saw this move and did the same. At the moment the naval barrage lifted, Rockwell’s little group was exactly opposite Dog White and Dog Green, the tanks firing furiously.”[16]

Aside from the obvious error (the DD tanks could not fire over the ramps of their LCT; Ambrose confused the DD/LCTS and the LCT(A)s), something is amiss here. None of Rockwell’s correspondence with Ambrose mentions anything written in that paragraph. Instead, Ambrose seems to have taken the experiences of another man and portrayed them as Rockwell’s—right down to the use of the nautical term ‘set’ for current direction—with some modifications to enhance Rockwell’s image . That man turns out to be Lt.(jg) Bucklew, whose LCS(S)s led Rockwell’s division from the 6,000 yard line to the beach, with one LCS(S) preceding each LCT to guide and to provide suppressive fires with rockets and machine guns. And it was Bucklew who was responsible for navigation during that phase. Bucklew’s account had this to say.

“4. . . . The LCT’s and LCS(S)’s then ran at slow speed to allow the LCT(A)’s of the first wave to catch up. Beach objects and Control Vessels were now visible, and the ascertaining of our position was now assured.

“5. Upon crossing the line of departure, beaching formation was taken by the LCT’s and LCT(A)’s, with LCS(S)’s slightly ahead and guiding them in. When about 2000 yards off shore, beach identification showed that the group was being set to the left. Course was changed to remedy this and speed increased to maximum to allow beaching on time.

“6. When about 400 yards out, directed two rockets to be fired as ranging shots. On observing them explode in the Target Area, all LCS(S)’s opened fire, firing quick salvos and maintaining a continuous fire for about five minutes. By continuously advising the leader of the LCT’s (LCT 535) as to what course to steer or what object on the beach to head for, and by constantly urging him to make his maximum speed, it was possible to hit the proper beach at nearly H-Hour. The leading LCT with DD tanks (LCT 535) beached at about 0632 hours . . . “[17]

The reports from Rockell’s OICs indicate they initially took fire in the vicinity of the Line of Departure, by which they actually meant the 6000 yard launch line. (The actual Line of Departure (LOD) was 3,500-4,000 yards out, but for some reason the DD/LCT crews all referred to the 6,000 yard line as the LOD). Fire became more intense and more accurate as they closed to the beach.

As with virtually all landings that day, the exact location they touched down can’t be precisely determined, although most leaders tended to believe they landed exactly on target, as Rockwell believed. A dissenting report came from Lt.(jg) J. L. Bruckner aboard PC567, which was the Primary Control Vessel for the Dog Green beach sector (Vierville-sur-Mere and the D-1 Exit), where four of Rockwell’s LCTs should have landed. That craft reported it was on station, 4,500 yards and at bearing of 210 degrees(T) from Dog Green at 0517 hours, well before Bucklew’s and Rockwell’s craft came along.[18] PC567’s report is a bit confusing. It first stated that it saw none of the four DD/LCTs slated for Dog Green and had no idea where they went. It went on to state that two ‘lost LCT(A)s’ reported in, and even though they were at the wrong beach sector, the PC waved them in. In fact, the two ‘LCT(A)s’ he mentioned (LCT-590 and LCT-591) were actually Rockwell’s two right-most DD/LCTs, the #7 and #8 in his formation.

Despite this error, PC567’s report contained two points of value. First, Rockwell’s right flank was off course so far to the east that two of the four LCTs (the #5 and #6 LCTs in the formation) missed reporting to the Primary Control Vessel and presumably landed in the next beach sector to the east (Dog White). CAPT Bailey, Commander, Assault Group O-2, observed in his own action report that PC567 “did not maintain station as accurately as it should.”[19] Since the current at that time was pulling PC567 to the east, that would mean Bucklew and Rockwell were even farther off course than suspected. And second, by the time they passed the Line of Departure, they were five minutes late. While this may have been at least partially overcome by Bucklew hectoring Rockwell to make best speed, Bucklew nevertheless reported they touched down two minutes late. It is not a terribly significant delay given the chaos of the landings. But it does tend to emphasize the meaninglessness of Rockwell’s oft-peddled claim that his was the first craft to beach on Omaha, touching down at 0629:30 hours.

Figure 4. The Landing. This image illustrates the beaching positions of Rockwell’s eight LCTs. The dashed LCT icons show the beach sectors they were intended to land on. The solid LCT icons represent the approximate sectors where they did beach - based on my interpretation of conflicting sources.

A Cruel Coast

The traditional account of the landing of the 743rd Tank Battalion has it that all 32 of the DD tanks of Companies B and C were delivered safely to the beach. That isn’t quite true. In drawing a contrast with the fate of the 741st Tank Battalion’s DD tanks, a bit of exaggeration crept into the story.

For one thing, ‘landing directly on the beach’ was a bit of a misnomer. With the draft of an LCT and the very gradual gradient on Omaha’s beach, the tanks would not land with ‘dry feet.’ They would be dropped into the surf, often with the water so deep it could drown out the tank engines. That is why the non-DD tanks, often called the ‘waders,’ were equipped with deep wading kits that protected the engines and had chimney-like ‘stacks’ that took the air intakes and exhaust vents above even the turret level. As a result, the DD tanks would need to keep their flotation screens inflated during beaching or risk drowning-out in the surf. However, this point was not appreciated by some the DD tank crews because the beach gradient at their training site in Torcross didn’t pose this problem. When the tanks beached there in training, they exited in shallow water. Misled by their training, almost all of the tankers deflated their skirts when they learned they would be put down ‘on the beach’, and the tankers aboard a couple LCTs even ditched ‘unneeded’ parts of their flotation equipment. As it would turn out, almost all of the tanks would exit in water requiring inflated skirts, and some would have to actually swim some distances—usually short—before touching sand. These errors would cost them precious time under fire while beached, and ultimately lives and tanks. It isn’t clear whether Rockwell and his OICs were aware of the different beach gradient at Omaha, or understood its implications. If so, it doesn’t seem to have been passed on to the tankers.

Company B’s Landing

The 16 DD tanks of Co. B were embarked on the last four LCTs in the column formation, which placed them on the right flank when the formation turned right into line abreast. The 743rd Tank Battalion S-3 (Operations) Journal includes an account of Co. B’s landing, stating they landed on Dog Green, which was their intended sector.[20] But given that only the farthest two LCTs on the right (#7 and #8 in line) encountered the Primary Control Vessel for that beach, and given this LCC was probably drifting too far east, it seems likely the lead two LCTs (#5 and #6) of that section landed on the neighboring Dog White.

The OICs of these four LCTs described their landings as follows (from right to left, facing the beach).

Ensign Robert B. Gilfert (OIC of LCT-590, #8 in line) reported:

“0630 Hit beach with rockets still falling around us.

“0630-0634 On beach waiting for tanks to go off. Were shelled by shore batteries and machine gun fire. Return fire with our 20mm gun and machine gun of first tank.

“0634 Last tank went off and we retracted from beach.”

Ensign George W. Novotny (OIC of LCT-591, #7 in line), provided the most bare-bones account, consisting of just these three paragraphs.:

“1. 0505 Received word to take tanks to beach. Tank men threw all launching gear overboard immediately.

“2. Hit beach Dog Green at 0630 and unloaded tanks. First tank was hit by 88 when five yards from LCT. Other tanks stopped alongside first tank.

“3. In my opinion launching gear should not be scuttled until last minute. If LCT should sink, tanks might float free or waves might permit launching at 1000 yards.”

Ensign Floyd S. White (OIC of LCT-713, #6 in column) ran into problems when beaching at H-5 minutes (0625 hours) about 50-75 yards shy of the Element C obstacles. When lowering the ramp, the ramp extensions were hanging askew, and the ramp was raised to discover the extension supports had been sheared off. The ramp was lowered again, but the lead tank commander hesitated; believing they would be dropped off in shallow water, his tanks had previously deflated their skirts. It took “about 15 minutes” to reinflate, but the supporting struts for the first tank’s canvas were not locked into place when the tank cleared the ramp. It sank straight to the bottom, the skirt not being strong enough to hold against the water pressure. After rescuing the tank’s crew, White retracted his LCT and beached again about 150 yards to the east, where “after a short delay, the other three tanks were successfully launched.” During this time, the ship was hit and set afire.” The choice of the word “launched” indicates they had to swim some short distance—presumably not very far. All these maneuvers resulted in the LCT not retracting the final time until 0710 hours, 45 minutes after its initial beaching.

Ensign William C. Cook (OIC of LCT-588, #5 in line) reported:

“At 0635 we beached as far as the ship could go on the beach. The captain thought the water might be too deep and would aid [?] them to inflate again. After doing this, they were able to reach the shore without any difficulty and the last I saw of them they were proceeding up the beach firing.”

From this it isn’t clear if any of these DD tanks had to swim.

The report of the first three LCTs reflect more intense enemy fire, as would be expected from the craft landing closest to the defenses of the D-1 draw. In addition to LCT-713 being set after, Gilfert on LCT-590 (the LCT closest to the D-1 Draw) lost three killed and two wounded during this beaching.

The account of Co. B’s landing contained in the S-Journal is brief and grim.

“Company ‘B’ landed on Dog Green beach, Normandy, France, at 0630 hours, 6 June 1944. Water was very rough, DD tanks were not landed. Heavy enemy fire was encountered, 88mm, heavy and light MG. Losses were quite heavy, 7 tanks lost, 3 officers and six enlisted men killed, and one officer wounded.”

The comment that “DD tanks were not landed” stands out, and the first instinct is to think it meant to say “were not launched.” As only one company officer remained in action by the end of D-Day (a second lieutenant) it’s possible that whoever penned this entry for Co. B was not bothered with precise wording. Yet William Folkestad, in his book The View from the Turret, claimed Co. B’s tanks did swim in.[21] And Novotny’s account of the tanks landing after throwing away their swimming gear indicates at least some of the tanks were landed in shallow water. But was he correct in thinking they survived the surf? We don’t know.

As mentioned in the previous installment, in the 1980s, Captain Robert Rowe, USN (Ret.) conducted a series of interviews with men of the 741st and 743rd Tank Battalions. One of the men he interviewed was Jerome T. Latimer (69 years old at the time of the interview on 5 August 1989). Latimer was the gunner in CPT Ehmke’s tank, and he gave a much different account of his landing.[22]

LATIMER: . . . I know that in the LCT I was at in the invasion, there were 12 of them that were killed. There were only 8 that got ashore.

ROWE: Now uh, tell me about that. Where were you, where were you hit?

LATIMER: We were hit as soon as we got off the LCT. I fired 3 shots and we got hit 3 times.

ROWE: When you went off the LCT, uh, where on the beach were you in relation to the Vierville Draw?

LATIMER: We were oh, just a little bit to the left of it.

ROWE: Just a little bit.

LATIMER: Uh, whatever direction that is. That would be east.

ROWE: Well that was east, yeah.

LATIMER: Yeah, we were a little east of the, of Vierville. That was exit 2, right? [Note: that would be Exit D-1. -CRH]

ROWE: Yeah. Were there any tanks to your right?

LATIMER: No. No tanks to the right. There were to the left but not to the right, that I can remember.

ROWE: Well - what I’m getting at – you were the right-hand flank, uh.

LATIMER: I think so. I think so.

ROWE: Uh, LCT coming in.

LATIMER: Yeah.

ROWE: Now, when you said that 12 men were uh, killed, uh, they were killed after the tanks had been, reached the beach.

LATIMER: Well, uh, no. No. They never got. What the hell, we only got, maybe 30 feet up the beach.

ROWE: Yeah.

LATIMER: And then the other tanks went off in the water. After, after Ehmke’s tank got off the, the LCT, the LCT began backing up and the other tanks went right down in the water.

ROWE: Now, when they went down in the water - -

LATIMER: There weren’t any tanks hit. They were, the tanks went in the water. They never had a chance.

ROWE: They sank.

LATIMER: Yeah. I know there was only, there was 12 of them killed out of the, out of the 20 that were on the LCT. And that’s a big chunk on that page where it shows all the guys that were killed from B-Company.

ROWE: And that was B-Company.

LATIMER: Yeah.

ROWE: Uh, you said the LCT, it beached for your landing.

LATIMER: Yeah. It hit the beach, down went the ramp. Now, this was told to me. I don’t know. I don’t remember even who told me. If you can find somebody else who was on the LCT. After we left, you know they, they throw out that uh, that wench I think they call it, or a hook.

ROWE: Yeah.

LATIMER: They throw it out and it digs into the sand. After the Captain’s tank went off the ramp and started up the ramp the LCT started backing up. That’s when the 3 tanks behind me went in the water.

ROWE: Three tanks, that’s 15 men. Twelve of those 15 were killed.

LATIMER: Twenty men, 20 men. There’s 4 tanks, 5 in a tank.

ROWE: Yeah, but you got off.

LATIMER: Well, there, yeah, I know, but there was 4 guys killed in the tank I was in, so there was 8 behind me that was killed.

As with almost all oral histories recorded decades after the war, memories and details are vague in some parts and seemingly razor sharp in others, and both just as likely to be in error as true. Deciding which details are reliable and which are false memories is a daunting task. Latimer’s insistence that the three tanks following his sank as the LCT retracted is tempered by his admission that he was told those details by somebody else (though eight of the men in those tanks were verified as lost on D-Day). Nevertheless, his account illustrates the much different perspectives between those left to fight, and those who dropped their loads and withdrew – a universal feature of military operations. I can attest to this from the time I hung suspended in my parachute harness from a tree a few hundred yards from the drop zone on an exercise the Air Force reported as a perfect drop.

The detail of the LCT backing up raises a possibility. When launching DD tanks, the American LCTs were required to be backing up at about 1100 RPM. So this might indicate the OIC thought the water was so deep that the tanks would have to swim, and was executing the launching maneuver. But were the skirts inflated, as was required for swimming? And if so, why then did the three tanks sink? Every source merely adds to the contradictions.

Unfortunately, this interview further confuses the matter of which LCT carried Ehmke. If Lattimer and Ehmke were aboard the right flank’s LCT as Latimer believed, it suggests Elder was in the corresponding LCT in the other division. That would be Dinsmore’s LCT-589. And that would support the idea that Dinsmore’s comment (“. . . at 0530 we decided the sea was . . .”) meant Elder made the landing decision and did so 20 minutes after Rockwell claimed.

If, on the other hand, the 743rd’s placement of company commanders mirrored that of the 741st, then Ehmke would have been in Novotny’s LCT-591, which links Novotny’s and Lattimer’s claims of the first tank being hit right after leaving the ramp. And although Novotny stated the other three tanks exited and stopped by the first, his exceedingly bare-bones account perhaps hinted at details he thought best be omitted. Two of his three short paragraphs dealt with the tankers’ decision to dump their landing gear. One could interpret this as an attempt to shift blame to the tankers for whatever befell the last three tanks as he withdrew from the beach (if indeed it happened as Latimer asserted).

And finally, Ehmke may have been aboard Cook’s LCT-588, as Cook referred to the Army officer aboard his craft as ‘captain’ twice. Ehmke was the only Army captain in this LCT section, so, unless Cook was confused by Army rank insignia (a real possibility) then this would mean it was Ehmke in Cook’s LCT.

As a result, we simply don’t know where Ehmke was, though I personally believe the evidence favors him in the right hand LCT.

Although Lattimer’s interview directly contradicts Rockwell and his OICs, there is support for it. In the Army’s Omaha Beachhead, it reported that:

“Company B, coming in directly in the face of the Vierville draw, suffered from enemy artillery fire. The LCT carrying the company commander was sunk just off shore, and four other officers were killed or wounded, leaving one lieutenant in Company B. Eight of that company’s 16 tanks landed and started to fire from the water’s edge on enemy positions.”[23]

This account confirms the loss of Ehmke and the four tanks on his LCT, although it attributes it to enemy fire LCT sinking the craft, which we know did not happen. In addition, Folkestad’s The View from the Turret also stated that one DD tank swam off the ramp.[24] Its LCT then reversed, and the following tanks drove off the ramp into deeper water and sank. So, perhaps we shouldn’t be too eager to discount 45-year-old memories.

One point is clear: Co. B’s tanks were not all landed safely on the beach, as popular history suggests. The question remains, what happened to the eight tanks that did not ‘land’? How and where were they lost.

Company C’s Landing

Although Rockwell directly commanded the division of eight LCTs carrying the 743rd’s DD tanks, he was aboard LCT-535, which was the far left (eastern) LCT in the four-LCT section targeted to land on Dog White beach sector. This section carried CPT Elder’s Co. C.

Tracking this section’s landing area is a bit difficult due to two errors in the operation plan for Assault Group O-2.[25] First, both the Landing Diagram and the Approach Schedules show the original placement of Rockwell’s two sections. As you will recall from the previous installment, Rockwell had embarked the two companies on the wrong LCT sections. By the time the error was recognized, it was too late to unload and reload, so RADM Hall had to issue a change to the Force O operations order switching the sections so that the tank companies would land in the proper sectors. NARA’s archival copy of the Assault Group O-2 order does not have Hall’s change annotated on the pages, so that must be taken into account.

Second, the Omaha Assault Area chart (also part of the O-2 order) mislabeled two beach sectors, transposing Dog White and Dog Red. Although the mistaken labels are crossed out and the correct labels written in Figure 2 (above), that correction may not have been completely disseminated. The 743rd Tanks Battalion’s S-3 Journal report for Co. C stated the company actually landed on Dog White and Easy Green. That seems to be an error. Those beach sectors were not adjacent, being separated by Dog Red, which would mean there was a 500 yard gap in the formation; they would only ‘be’ adjacent if the person making the entry in the S-3 Journal was referencing the uncorrected Omaha Assault Area chart. Neither Rockwell nor his OICs hint at this break in formation, so perhaps whoever authored the entry for D-Day was working off an uncorrected Omaha Assault Area chart. As we continue to uncover more inconsistencies and errors in Rockwell’s reports, I can’t rule out such a gap, but I think it most likely the company landed spread across the adjoining Dog White and Dog Red sectors. Or, less likely, they were farther off course, landing on the adjoining Dog Red and Easy Green. They were in good company, as almost every craft in the first four waves had been swept to the east by the current.

The OICs of this section described the landings as follows:

Ensign Earl J. Dinsmore (OIC of LCT-589, #4 in line) reported that his craft touched ground at 0630 a short distance east of Hamel-au-Pretre. That would place him somewhere near the middle of Dog White or a bit farther to the east. As he was the right-flank LCT of Rockwell’s section (i.e., the other three LCTs were stretched out to the east), this would confirm the company landed astride the Dog White/Dog Red boundary.

Dinsmore’s landing almost came to grief as a result of the actions of the embarked tankers. According to his report, the tankers stripped off the gear needed for swimming and tossed it overboard, believing it was not needed. He didn’t specify how much was stripped off (or how much could have been, under the circumstances), but the rash action would jeopardize the tanks’ survival if they landed in water as deep as had LCTs-586 and -587, both of which needed their tanks’ skirts inflated in the six-foot water. But fortune was smiling on these tankers, for the moment. Dinsmore recorded:

“The tide had just begun to rise and immediately our tanks were off the deck. They were in about 3 feet of water and about 15 yards from the first row of obstacles.”

In Dinsmore’s case, his LCT didn’t attract enemy fire until they were turning away from the beach.

Lieutenant (junior grade) Albert M. Demao (OIC of LCT-587, #3 in line) reported landing under heavy fire, but with more complications.

“2. The first two DD tanks were launched in about 6 feet of water on Dog White Beach at 0635. Shrapnel was falling all over and one piece tore a hole approximately eight inches in diameter in the canvas on top of the front left corner of the third tank’s screen, resulting in deflation of several of her rubber pillars and possible slight injury to the one soldier standing on the tank. He stated it would be impossible to launch the tanks, and LCT-537 retracted from the beach.

“3. At 0643 the 587 beached again and launched the last two tanks in slightly shallower water without accident. All four tanks touched bottom almost immediately after launching and waded ashore with no difficulty.”

Demao’s wording indicates, again, the tanks needed to swim a short distance.

The only tanker from Co. C reported wounded while abord an LCT was Sergeant Gerald M. Bolt. He was climbing into the turret of his tank shortly before landing when a shell shattered his left leg. He refused evacuation and had his gunner lash his wounded leg to the recoil guard of the tank’s 75mm gun so that he could remain standing in the commander’s hatch. He fought his tank for six hours before he sought medical aid.[26]

Ensign Joseph M. Carey (OIC of LCT-586, #2 in line) unloaded his tanks while under heavy fire. He recorded:

“The army unit went off in about six feet of water with their sides inflated and cleared the ship without damage.” And later in the report, “When I left the beach, the tanks were in a group and half under water and were firing.”

Ensign Albert J. Pellegrini (OIC of LCT-535, #1 in line) merely recorded:

“Putting ashore all 4 tanks and personnel safely, the ramp was raised and the 535 retracted from the beach and started for the transport area to take on her second load.”

Although the four LCTs of this section encountered scattered shelling as far out as 5-6,000 yards, when they beached they faced less deadly concentrations than the other section Three of the four OICs reported receiving heavy fire from the enemy, but none reported damage to ship or crew, with just SGT Bolt of the tankers being wounded. Only Pellegrini in LCT 535 failed to mention enemy fire while beaching; perhaps being the farthest LCT from the defenses of the D-1 draw paid off.

Thus, according to the reports of these four OICs, all 16 tanks of Co. C made it off the LCTs safely and in condition to fight. But were those reports correct? Under fire and anxious to pull out, were they reliable witnesses to events past the end of their ramps? Judging by the S-3 Journal’s entry for Co. C, yes, they were.

“Company ‘C’ landed on Dog White and Easy Green [read Dog Red? -CRH] beaches at H-6. Although water was unusually rough there were no losses on landing. Upon approaching the beach we were met with fire from individual weapons, 155mm, 88mm, and machine gun fire. One tank disabled.”

One additional tank was lost when the life raft on its rear deck caught fire, which spread to the engine compartment. Four men and one officer were wounded and evacuated that day. So, it seems all of Co. C’s tanks did get off in good order, touched sand almost immediately and entered the fight.

Or perhaps it wasn’t that simple. Captain Rowe interviewed two Co. C tankers: Clyde E. Hogue and William L. Garland. They paint a significantly different picture. The following are excerpts from Hogue’s interview (age 65 at the time of interview on 25 February 1988):[27]

“HOGUE: . . . And just about that time there was a LCT pulled up beside us and it’s whole deck was loaded with rockets. And they pulled up within, oh within 50 yards of us and fired all those rockets off. And course, I had never seen nothing like that and I thought that was amazing. And then very little, a little bit after that, why they dropped the ramp and luckily our LCT took us in closer. They didn’t dump us clear out.

“ROWE: Now, where did they dump you?

“HOGUE: They dumped me, I didn’t have to swim too far before I touched down. I would say, I wouldn’t doubt I was maybe, uh, oh, probably less than 1000 yards, when they run us off. And after we, course before that I got hit. And my tank commander was hit. And he, he strapped himself to the turret and he stayed with us till a little bit after noon.

“ROWE: Yeah.

“HOGUE: SGT Bolt.

“ROWE: Yes. I got him being hit on the 6th of June. Rather interestingly, I don’t have you. Now, uh, you say you were hit?

“HOGUE: Not then.

“ROWE: Oh.

“HOGUE: Not then, no.

“ROWE: Oh, when were you hit?

“HOGUE: July the 8th.

“ROWE: Okay, that’s why I don’t have it. Okay, we’ll get that later. Alright, you come in. You drop the bow ramp.

“HOGUE: They dropped the ramp. The first tank - -

“ROWE: The first tank went off.

“HOGUE: And what happened to it I don’t know. I never seen it again.

The detail of SGT Bolt’s wounding ties this to Lt.(jg) Demao’s LCT-587, which, Demao reported, landed its tanks in “about six feet of water.” That is quite a discrepancy between the two accounts.

The rocket-equipped LCT (known as LCT(R)) detail should help with the distance issue. According to CAPT L. S. Sabin, commanding the gunfire support task group (CTG 124.8), his LCT(R)s were supposed to “move in and delivery rocket fire when the leading wave was about 300 yards off shore.”[28] If that unfolded as planned, the Hogue would have been launched inside 300 yards from the beach. Alas, nothing was that well organized or smoothly functioning that morning. CAPT Sabin had positioned himself 1,000-2,500 yards off Dog Red beach sector. He observed “that the LCT(DD) were not in a wave formation and that there was a general mix-up of all craft.”[29] Lacking a coherent wave to key on, we can only guess how far offshore Hogue’s craft was when the LCT(R) decided to fire.

Rowe’s second Co. C interview was with Garland, who served as the gunner for his tank, and believed he was the second tank to touch down on the beach that day. His interview placed the launching even farther out (age 65 at the time of interview on 19 August 1988).[30]

ROWE: Now when you started up the tanks did you know that you were going to be landed on the beach, or did you think you were going to swim in?

GARLAND: They told us – well, we would have to swim in. We uh, we got off the boats at 6,000 yards out, and floated in.

ROWE: Oh.

GARLAND: I don’t know whether you got that information or not.

ROWE: I got that you were taken right into the beach.

GARLAND: No. We were not. We floated in. We lost a few tanks - -

ROWE: Well, yeah, you floated in, but uh, you only had about 1000 yards to float in.

GARLAND: No, we had more than that. You couldn’t see the beach.

ROWE: You couldn’t.

GARLAND: No. You couldn’t see the beach.

ROWE: You were in C-Company in the 743rd.

GARLAND: C Company, yeah. No, we could not see the beach. We were out further than that.

ROWE: Well, yeah, when you say you were out further than that when you were launched?

GARLAND: Yes, when we were launched.

ROWE: That is contrary to the information I have.

GARLAND: Yeah, we were out further than that.

ROWE: You only lost 4 tanks in the landing going in.

GARLAND: Right, right. Till we hit the beach.

ROWE: And uh, if you swam in, uh, you would have had more than that.

GARLAND: Yeah. Well, as I say now, you’re talking to an 18 year old boy here that is, uh, in his first battle uh, you know.

ROWE: Oh, yes, I know what you mean.

GARLAND: Everything looks larger than it is.

. . .

ROWE: Now, when you landed, tell me what happened. What – where was the position of your tank in your LCT?

GARLAND: I was in the 2nd tank. Uh, we had 1 tank here and we had them staggered, and I was over here.

ROWE: You were the second off.

GARLAND: 2nd one.

. . .

ROWE: Okay. The 1st tank goes off. Tell me what the 2nd tank does.

GARLAND: Well, after the 1st tank cleared the ramp, the 2nd tank went off, and the 3rd and the 4th and the 5th and the 6th.

ROWE: Yeah.

GARLAND: Then we headed for shore.

ROWE: You said that you had longer than 1000 yards.

GARLAND: It was longer than 1000 yards, yeah.

ROWE: Okay. Uh, what did you do when you got ashore.

GARLAND: Well, the first thing we did was to drop the canvas as soon as we got clear of the water. As soon as treads in the sand, we dropped the canvas, and started firing, of course.

ROWE: That’s one of the things that I have to worry about is that uh, you started swimming to the shore, and then coming up out onto the beach what you did.

GARLAND: Yeah. Well, as soon as we hit the sand, you could feel it. When the treads hit the sand, why, the tank commander deflated the tubes on the canvas and we were in firing position.

Remarkably, these two accounts insist that, contrary to every contemporary official report and every subsequent popular account, at least some of the 743rd‘s tanks were launched to swim ashore from 1,000 yards or more. This is significant. It doesn’t affect the tactical outcome, as the bulk of the DD tanks of the 743rd made it ashore on D-Day, regardless. Still, this revelation would completely alters the official judgements on Barry, Thornton, and Young.

But how much weight should we grant Hogue’s and Garland’s account? They were clearly incorrect on some details, such as Garland’s statement that there were six tanks on his LCT or that the LCT was crewed by British sailors (not included in the quoted except). Oral histories recorded decades after the fact are notorious historical minefields, and picking a path through them is difficult. Should we grant them more credibility than the contemporary reports of the LCT OICs? Were Hogue and Garland wrong? Or were they right, meaning the four OICs may have sanitized the inconvenient details that did not fit Rockwell’s ‘party-line’ version of events? The fact that Lattimer’s interview, too, has independent support suggests we should not simply dismiss the accounts of these senior citizens, either.

I generally favor official contemporary records over oral histories recorded decades later, and there are many reasons for this. But in this case, I will reserve judgement for a very good reason. In this case, a monkey wrench was thrown into the historical gears from a quite unexpected source, and it deserves serious consideration.

The Monkey Wrench with Rockwell’s Name on It

Earlier in this article, while discussing the approach to beach, I quoted from the oral history Rockwell provided Stephen Ambrose. By and large, the central details of that transcript were consistent with those of his official report. And they should be. Rockwell reviewed the transcript multiple times and provided corrections and clarifications. He also provided additional print sources which featured his D-Day exploits. The transcript was revised at least twice over two years for accuracy. So, there is every reason to believe the oral history was as accurate as Rockwell could make it.

When I quoted from that transcript earlier in this article, I omitted two passages (as indicated by the ellipses). It’s time to revisit that quote in its full format. That quote is reproduced below with the omitted potion included and highlighted in red.

“As noted earlier, the original plans were for our landing craft to proceed parallel to the beach at about 5,000 yards off turn right 90 degrees and proceed toward the beach to the launching point where these tanks would go off the end of our ramps and over the delicate launching gear one by one into the sea with their shrouds inflated and their twin screws propelling them to the beach. But the sea was running very heavily, and after launching one or two tanks and having them become swamped with water and go down, I was in communication by low power tank radio (even though all communication was forbidden prior to H-hour, the decision to launch or not to launch into the sea was absolutely critical to the success of the Invasion. We broke radio silence. What the hell, by now the Germans were aware what was about to happen) with a Captain Elder, of the 743rd tank battalion. We made the joint decision that it would be insane to launch any more tanks and the signal was given by tank radio to all craft to cease the launch. The next signal to all our craft and to the tank commanders that we would proceed to the beach, which we did. And when our landing craft drove up on the shore, the ramps were dropped and the tanks drove off, with their shrouds down, ready to provide coverage to the infantry units that were to come in behind them.”[31]

This was quite simply an astounding revelation. In his 14 July report, Rockwell delivered a stinging rebuke to the decision-makers in Assault Group O-1, essentially stating that only a fool would not have realized the seas were too rough to launch the DD tanks. Yet 48 years later he disclosed that he, too, permitted his LCTs to launch some number of tanks—which sank in the ‘obviously too rough seas’, of course.

Rockwell’s oral history is precise (if not accurate) on all minor details, right down to the second he claimed he beached. I find it odd that he could only vaguely number the lost DD tanks as “one or two.” That’s the kind of imprecise language people tend to use when trying to minimize embarrassing details.[32] This indicates to me the number of lost tanks was at least a bit higher than Rockwell admitted - perhaps all the tanks in one LCT.

Essentially, Rockwell admitted here that he was guilty of almost every transgression that Barry was censured for. All the commands to Rockwell’s OICs came through the Army radios, not through Navy communications, and we have no indication Rockwell gave any of those orders. He certainly never claimed he did. The best he could claim was that he and Elder communicated and were in complete accord after one or two tanks had sunk. Rockwell positively stated he only contacted Elder after the tanks had been launched and sank, so the order must have come from Elder, with Rockwell a silent observer - just as Barry had stood by as the tanks were automatically launched in O-1. In other words, the actual launch decision in Rockwell’s division was solely in the hands of the senior Army officer - just as Barry said was decided in the Portland meeting, and just as Rockwell himself recommended in his 30 April training report. Indeed, since Rockwell had no role in either launching the tanks or aborting the process, then the communication with Elder was almost certainly initiated by Elder as he asked to be taken in to the beach.

The only difference between the occurrences in O-1 and O-2 was that the man on the scene in O-2 was able to recognize the error of the launch decision and to reverse it; but again, this was almost certaily Elder. The reason that did not—could not—happen in O-1 was because the LCT carrying Thornton had become lost and was not present at the launch line when the tanks rolled off the ramps. And the proximate cause for that LCT becoming lost can be laid at Rockwell’s feet: he switched out the OIC of that craft less than three hours before the sortie. While that decision may have been necessary, it was not timely and contributed to failure. Rockwell had not paid close enough attention to the organizing of the other half of his command, and that, coupled with his other errors in planning, produced the cascading series of errors that doomed the DD tanks of the 741st Tank Battalion. And, it now appears, his actions came close to doing the same for the 743rd.

Having said all of that, there are a couple of points to address. The primary issue is, again, the timeline. DD tanks were due to be launched at 0535 hours. That would give the slow swimming tanks 45 minutes to reach the beach at 0620 (H-10). And that means Elder’s aborted launches should have occurred close to 0535 hours as well (depending on whose watch we’re talking about). Yet two OICs stated they received word not to launch at earlier times: 0500 hours (LCT-590), 0505 hours (LCT-591), which as we have already seen was very close to Rockwell’s time for the decision (0505 hours). Yet those were the only two who provided times corroborating Rockwell’s claim. Two OICs made no time reference for this decision (LCT-587 and LCT-713). Three (LCT-535, LCT-586 and LCT-588) stated they were informed after they turned left at the 6,000 yard line or just prior to coming into line abreast. And LCT-589 stated they had already turned into line breast at 0530 hours, “when we decided the sea was too rough for the launching pf the DD tanks.” Given the imprecise and wide range of recorded times, the window does permit one or two tanks being launched, probably from one of the leading LCTs - where Hogue and Garland were.

So, how do we reconcile the conflicting reports, especially those of Rockwell himself? And what in the world really did happen with the DD tanks of CPT Elder and Ehmke? Should we believe Rockwell’s original version, as supported by some of his OICs? Or should we believe Rockwell’s report from 50 years later, which was at least partially backed by some of his OICs and the memories of two of the men who rumbled down the ramps and into the sea that morning? And what to make of the line in the Co. B entry for the S-3 Journal that the DD tanks were not landed. Mistake? Or accurate, at least in part? And what of the LCT that drooped out of formation, got lost and arrived late?

At the outset of the previous installment, and this one as well, I cautioned I would expose the reader to the sleazy underbelly of historical research. A swamp of contradictory statements from sources both contemporary and far more recent. Authored by men who were, by turns, brutally honest, self-serving, old, and possibly confused. As confounding as reconciling this is, it becomes virtually impossible due to the total absence of testimony from key Army voices who died during the landings or shortly thereafter.

There is no clear truth here. All you can do is evaluate sources and try to determine which are more likely to be somewhat less wrong. Anyone who claims to have the ‘real story’ is fooling himself. But amid this fetid swamp of mis-history, perhaps we have the explanation as to why popular histories have simply followed the official—but obviously flawed—versions forward by the younger Rockwell and RADM Hall. As bad as those versions were, they at least offered a simple, clear (albeit wrong) tale to tell.

For the moment I will keep my conclusion to myself, saving them for the next installment when we wrap up the saga of the DD tanks of Omaha Beach. In the meantime, I encourage the readers, as an intellectual challenge, to take a stab at making sense of all of this . . . and leave your comments.

Acknowledgements.

While researching this Omaha Beach Series, I have come in contact with several excellent researchers, and as good researchers do, we shared our finds. In the case of this DD Tank series, I owe a tremendous debt to Patrick Ungashick whom I stumbled upon while we were both delving into the subject. Patrick had managed to dig up a trove of Lt. Dean Rockwell’s personal papers which Rockwell had provided to Steven Ambrose. Any serious study of the DD tanks question must include these Rockwell papers, and I would have been lost without them. My sincere gratitude to him. Patrick has a book coming out this June which uses WWII case studies as a teaching vehicle for management decision making. One of those case studies focuses on, of course, the DD tanks at Omaha Beach. Patrick and I take somewhat different approaches to our analyses, and our conclusions are somewhat different, but I wholeheartedly recommend his upcoming book: A Day for Leadership; Business Insights for Today’s Executives and Teams from the D-Day Battle, or one of his other fine books. Thanks, Patrick!

In addition, my thanks to Barry Hartman for the use of the photo of the knocked out DD tank on the Dog Green beach road. It was taken by his father, Tech/3 Burton Hartman who was a member of Detachment Q, 165th Signal Photo Company. Barry is in the early stages of putting together a documentary of his father’s WWII experiences. If you would like to help document history, consider donating to his GoFundMe account to help get it off the ground.

Endnotes:

[1] RADM Hall’s endorsement to Rockwell’s 14 July 1944 report credits only Rockwell and Ensign Pellegrini for the decision, omitting Elder completely.

[2] As discussed in the previous installment, the DD/LCTs has been organized anticipating a specific approach formation during the approach to the beach. However, the operations orders for the two assault groups, which specified a different approach formation, were published late, and after the DD tanks had been embarked. The new approach formation resulted in the division leaders being abord the wrong LCTs.

[3] Lt.(jg) J. E. Barry’s Action Report, dtd 24 July 1944, for the time of the command change. It is held in the Robert Rowe papers at the U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center, Ridgeway Research Room, Carlisle Barracks, PA. See also Ens R. J. McKee’s report, subj: DD Tanks, Launching of, dtd 20 July 1944, for Rockwell’s role in ordering the change of OICs. Also held at Carlisle.

[4] COM LCT(6)GR 35 (Lt.(jg) Dean L. Rockwell) memo, subj: Launching “DD” Tanks on D-day, Operation Neptune, dtd 14 July 1944. NARA, RG 38.

[5] CTG 124.4/COMTRANSDIV 3 (CAPT Bailey) order No. 4-44, dtd 27 May 1944. NARA: RG 38, Box 318

[6] Rockwell, op cit.

[7] Dean Rockwell Oral History. Transcribed 6 Dec 1990, Revised 2 Nov and 30 Nov 1992. Eisenhower Center, the University of New Orleans.

[8] The Action Reports of all LCT OICs discussed in this article are held in the Robert Rowe Papers, at the U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center, Ridgeway Research Room, Carlisle Barracks, PA.

[9] Deputy Commander, Assault Force O-2 (CTG 124.4.3, CAPT Bailey) memo, subj: Action Report – Operation Neptune, dtd 4 July 1944. NARA, RG 38.

[10] Commander, Gunfire Support Craft (CTG 124.8, CAPT Sabin), Action Report – Operation Neptune, dtd 3 July 1944, pg 16. CAPT Sabin reported Landing Craft, Gun (LCG(L)-449 and LCT(A)-2008 had also mistakenly headed toward Utah Beach.

[11] Folkestad, W., The View from the Turret: The 743rd Tank Battalion During World War II, Burd Street Press, Shippensburg, PA, pg. 7. The Hansen interview is not further identified but appears to have been one of Rowe’s.

[12] United States Army; Robinson, Wayne; and Hamilton, Norman E., Move Out, Verify: The Combat Story of the 743rd Tank Battalion (1945). World War Regimental Histories. 66. Pp 176, 177 and 180.

[13] Rockwell, Oral History, pp. 6-7.

[14] COM LCT(6)GR 35 (Lt.(jg) Rockwell) memo to Commander, ELEVENTH Amphibious Force. Subj: Results of Training, Tests and Tactical Operations of DD Tanks at Slapton Sands, Devon, England, during the period 15 March – 30 April 1944, dated 30 April 1944, para 8(b). NARA, RG407, Entry 427d.

[15] Rockwell, D, letter to Stephen Ambrose, no subj, dtd 3 Aug 1998. Eisenhower Center, University of New Orleans.

[16] Ambrose, Stephen, D-Day, June 6, 1944: The Climactic Battle of World War II. Touchstone, New York, pg 273.

[17] Lt.(jg) Bucklew’s report was quoted in detail in Commander, Task Group 124.4 (CAPT Bailey), Report and Comments on Lessons Learned in Operation Neptune, dtd 20 June 1944, pp. 7-9. NARA, RG 38.

[18] USS Thomas Jefferson (Lt.(jg) Bruckner, Dispatching Officer aboard PC567) memo, subj: Operation NEPTUNE – Report of, dtd 7 Jun 1944. NARA, RG 38.

[19] Op cit. CAPT Bailey’s comment is on pg. 10. Lt.(jg) Bucklew also commented on PC567’s drift to the east on pg. 9.

[20] 743rd Tank Battalion memo to Commander, 30th Infantry Division, subj: Action Against Enemy, Reports of/After Action Report, dtd 20 Jul 1944. Ike Skelton Combined Arms Research Library, Fort Leavenworth, KS. https://cgsc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p4013coll8/id/3810/

[21] Op Cit. Folkestad, W., pp 6-7.

[22] Transcript of Interview with Jerome T. Lattimer, CPL, dtd 5 Aug 1989. Robert Rowe Papers, 1944-1991. U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center, Ridgeway Research Room, Carlisle Barracks, PA. Box 9.

[23] U.S. Army Center for Military History, Omaha Beachhead: 6 June-13 June 1944, Battery Press, Nashville, TN, 1984, pg. 42.

[24] Op Cit. Folkestad, W., pg 4. Folkestad said this was a Co. C tank, but I believe that was an error. He did not cite a source for this anecdote, but quoted Rowe’s interview with Co. B’s Lattimer for the next paragraph of the narrative. Clearly Lattimer was the source for this anecdote, as the details match.

[25] Op cit. CTG 124.4/COMTRANSDIV 3 (CAPT Bailey) order No. 4-44.

[26] Op cit. Move Out, Verify, Pg. 24.

[27] Transcript of Interview with Clyde E. Hogue, T/5, dtd 25 Feb 1988. Robert Rowe Papers, 1944-1991. U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center, Ridgeway Research Room, Carlisle Barracks, PA. Box 9.

[28] Op cit, Sabin, pg. 16.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Transcript of Interview with William L. Garland, PFC, dtd 19 Aug 1988. Robert Rowe Papers, 1944-1991. U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center, Ridgeway Research Room, Carlisle Barracks, PA. Box 8.

[31] Op cit. Rockwell’s Oral History, pp 6-7.

[32] See also LTC Skaggs vague reference to “most” of his adrift DD tankers surviving and being picked up by rescue craft. Commander, 741st Tank Battalion, memo, subj: Comments and Criticisms of Operation “NEPTUNE, dtd, 1 July 1944. Online at the Colonel Robert R. McCormick Research Center’ Digital Archives, First Division Museum at Cantigny. Record Group 301-INF(16)-3.01: Lessons Learned

The Duplex Drive Tanks of Omaha Beach, Part (d) The Debacle Off Easy Red and Fox Green

In the early hours of the 5th of June 1944, the 64 Duplex Drive Sherman tanks of the 741st and 743rd Tank Battalions left Weymouth Bay aboard 16 Landing Craft, Tanks. It was a rough crossing, testing both men and the landing craft. But far worse trials awaited the tankers the next morning as they had to fight a deadly battle with the seas off Omaha Beach before they could even come to grips with the enemy. This installment focuses on the ordeal of the 741st Tank Battalion, which was slated for the eastern half of Omaha Beach. Specifically, it details how the errors in planning and coordination stacked the deck against these men, and examines the full story behind the decision that saw 27 of their 32 tanks sink in the waters off Omaha Beach.

An M4A1 Sherman DD tank that sank in 90 feet of water off Omaha Beach on D-Day. It is on display at the Musee des Epaves Sous-Marines du Debarquement, Port-en-Bessin-Huppain, France [Copyright Normandybunkers.com- image used with permission.]

Author’s Note

The usual role of the historian is to peer through the smoke and confusion of battlefield and assemble a direct and simple narrative that even the casual reader can understand and enjoy. But what if the essence of the matter is confusion? What if the attempt to simplify, instead fundamentally changes or nullifies the reality? That is the challenge with the next two installments of this series. The various orders and plans were contradictory and inadequately coordinated. The official reports of the action were penned in the aftermath of the debacle, when many of those involved were seeking to avoid blame or point the finger at others. These accounts were often self-serving, usually contradictory, generally limited in details and scope and always to be viewed skeptically. Instead of truth, we must wade through a morass of claims and counterclaims, few of which can be factually validated. In such a case, simplification can only result in distortion shaped by one’s own biases. I have, therefore, found it necessary to lay out all the information as we know it and examine each point in detail. It may confuse more than clarify, but the very essence of this matter is confusion, and careless clarification can only mislead. Yes, this is the historian’s equivalent of making sausages, complete with ugly details. It isn’t pretty, but it is necessary to portray the reality. So, dear reader, don your butcher’s apron and face shield, it’s going to be messy.

Sortie and Sortie Again

It was early in the morning of 4 June 1944 when the great assemblage of shipping in Weymouth began to weigh anchor and set course for Normandy. With every preparation made and all equipment and vehicles in the best possible order, the armada headed through the gap in the minefield at the entrance of the bay. Convoys had been formed from these vessels, with departures staggered based on their speed and the order in which they were scheduled to arrive off the coast of France. As the convoys passed beyond the narrow entrance channel, the vessels shook themselves out into formation, often jostling their way through other craft intent on the same business. This was the bulk of the naval force for the Omaha Assault Area, and it would be joined by smaller convoys from other ports. Four other armadas, each of similar size and composition were sailing from yet more ports, destined to the other four assault beaches.

The long-awaited invasion was underway, inspiring both relief that the endless waiting and training was at last finished, and dread at what was to be encountered in the next few hours. Regardless of human emotions, the coiled spring that was the Allied invasion force was being released.

But not for long.

The 16 Landing Craft, Tanks (LCTs) carrying 64 Duplex Drive (DD) tanks sortied a few hours before dawn, initially proceeding in a single-column formation through the narrow harbor entrance. With a blackout in effect, radio silence imposed, and a pitch black night, confusion and collisions abounded. Once clear, the 16 craft—at this stage under the direct command of Lieutenant (junior grade) (Lt.(jg)) Dean Rockwell—would form into four columns, each of four LCTs. Two columns were slated for the eastern half of Omaha Beach (part of Assault Group O-1), and the other two columns for the western half (in Assault Group O-2). A full 24 hours were allotted for the trip to the Transport Area off Omaha Beach, and even that was cutting it close given the slow speed and poor seakeeping abilities of the heavily-loaded LCTs. Contrary to the recommendations of Rockwell and Major (MAJ) William Duncan (the executive officer of the 743rd Tank Battalion and commandant of the DD tank school) that no other cargo be loaded on the DD/LCTs, several jeeps and trailers had been added to each one, increasing the weight and dangerously crowding the DD tanks with their delicate canvas skirts.[1]

At 0640 hours, just about three hours into the voyage, the column received a message stating “Post Mike One.”[2] It was the code ordering a 24 hour delay, made necessary by an unfavorable weather forecast. With some difficulty (not all the elements received the message) the armada was turned around and proceeded back to Weymouth Bay, which again became a mass of confusion as a similar scene of jostling craft again took place, this time as berthing spots were reclaimed. The 16 DD/LCTs managed to find mooring points in Portland Harbor, nestled inside a breakwater in Weymouth Bay.

The confusion was about to be greatly compounded. A convoy destined for Utah Beach was unable to make it back to its original port farther west along the British coast, and it, too, tried to straggle into Weymouth Bay, finding anchorages where it could. Many of these craft had to anchor just outside the entrance to Weymouth Bay, and others of this convoy were still milling about the entrance to the bay when the invasion was relaunched in the early hours of 5 June.

Despite the chaos, Rockwell managed to find a bright side; the delay permitted urgent repairs. Three of his 16 craft were already mechanical casualties. Two had their landing gear (the ramps and ramp extensions) damaged by collisions and one needed a new engine.[3] Navy maintenance teams and the LCT crews managed to make repairs in time for the next sortie.