The Duplex Drive Tanks of Omaha Beach, Part (f) Conclusions and Final Thoughts

This is the concluding installment in my six part dep dive into the facts surrounding the employment of Duplex Drive tanks at Omaha Beach. In this analysis I recap the roles played by the prominent figures in the saga and the degree to which they contributed to the outcomes on D-Day. Also is included a brief review of how the commanders at Utah, Sword, Gold and Juno Assault Areas planned for employment of their DD tanks, and how the results at those beaches compared to Omaha.

The saga of the Omaha Duplex Drive tanks is in many ways symbolic of Operation Neptune itself. The need for these tanks was a direct result of the alliance’s strategic dilemma: despite nominally giving the invasion high priority, it was unable or unwilling to commit sufficient naval assets to the task. One of the results of this mismatch between strategic lines of effort and force priorities was the critical shortage of bombardment ships for Neptune. The eventual solution was to seize on an experimental concept, throw it in on the first wave of the assault, and hope for the best.

On the one hand we see in this the genius of innovation, flexibility and industrial brute force, all key components of the eventual Allied victory. The fact that the industrial base could convert 200 Sherman tanks into duplex drive variants and ship them to the United Kingdom in a matter of just a couple months was an astounding feat (not to overlook the conversions being produced in the UK). But that kind of improvisation often contains the seeds of failure, usually in the form of inadequate engineering or inadequate production quality. And so it was here. The design of the duplex drive kit was so immature that the first thing they had to do when they reached the United Kingdom was apply fixes to the struts to keep them from collapsing. Given the brutal nature of the English Channel, that ‘fix’ would fall short.

An Extract from Commander, 3rd Armored Group memo to MG Huebner, Commander, 1st Infantry Division, addressing DD tank training. This paragraph highlights the deficiencies of the newly arrived duplex drive Sherman conversions.

And that illustrates the leitmotif which wove through the Neptune planning. It was in many ways characterized by a large scale effort to improvise solutions to problems which sprung, as often as not, from poor strategic planning and the enemy’s refusal to passively await a beating. In virtually every category, the planners were scrambling to find the means to achieve the ends. Bombardment ships, landing ships, landing craft, escorts, minesweepers, transport aircraft for airdrops - all were critical shortages. Sometimes units or materiel were found to fill the gap, but these were usually ad hoc, untested or ill-trained. And too often the invasion had to make do despite the shortages.

It is important, however, to keep this in context. War-by-alliance is a difficult endeavor, especially one being fought across the entire globe in numerous theaters, each with its own unique demands, and all clamoring for a share of vast, yet limited resources. The point of the preceding paragraphs is to highlight the limitations which hampered the planning and execution of D-Day. It is not intended to lodge a blanket indictment of LTG Morgan’s COSSAC or GEN Eisenhower’s SHAEF. Nor is it intended to criticize the wisdom of the Combined Chiefs of Staff or the political leadership of the allied nations. Certainly, individual decisions by each and every one of those bodies can be questioned, and sometimes, as they say, ‘mistakes were made.’

But that isn’t the point. All war is characterized by friction, inadequate resources, tradeoffs and sub-optimal solutions (the least bad options). Operation Neptune was no different. And despite the challenges and near chaos, it did succeed. Not as cleanly or easily as planned (or hoped), but assaults on defended shores seldom are.

The question here, however, is how effective were the commanders, their staffs and the executing units in coping with the limitations to make it all work. In some cases it was a matter of doing a familiar mission, but with green, perhaps ill-trained, units. In other cases, it was making the best of the least bad alternative. Which brings us back to the DD tanks. A new ‘gimmick’, inadequately designed and tested, hurriedly produced, not well suited for the waters in which it was to operate - yet necessary, if not vital, for want of a better solution. They were indeed the least bad solution. But that didn’t make them the wrong solution.

So, it is now time to recap the preceding five installments with an eye on how well each echelon addressed, helped or hindered the effort to land 64 swimming Sherman tanks on Omaha Beach at 10 minutes before H-Hour.

What I hope I have provided in this series is the most comprehensive body of research on the DD tank effort to date, as well as a detailed analysis of that information. To repeat a caution from an earlier installment, the saga of the DD tanks is so thoroughly replete with conflicting reports and questionable firsthand accounts that any conclusion depends entirely on which imperfect source you reject, and which you decide to accept. Others will no doubt weigh the sources differently and come to different conclusions. What follows represents my evaluation after more than a year’s study of the topic.

Two of three DD tanks landed directly on Easy Red Beach Sector by Ensign Henry Sullivan’s LCT-600. Photo by Robert Capa.

The 6,000 Yard Line.

One of the more curious aspects of the DD tanks saga was the disregard paid to the advice of the two men who had become experts in their use. After conducting an intense six-week training course for DD tanks and LCTs, Lt.(jg) Dean Rockwell and MAJ William Duncan were as much of experts on the matter as anyone else in Western Naval Task Force. Duncan ran the school to train the DD tankers and Rockwell’s LCTs supported the training. At the end of that training program, both men submitted reports. Rockwell noted that DD tanks “can be launched 3-4,000 yards from shore and reach a specified beach.” [1] Duncan noted that the tanks had been launched from as far out as 6,000 yards, but also noted that in launches of more than 4,000 yards out, six cases of non-fatal carbon monoxide poisoning occurred.[2] He therefore recommended they “not be launched more than 4,000 yards from the beach.”

Having received recommendations from their own designated experts, the powers that be ignored that advice and decided the appropriate launching distance would be 50% to 100% farther than recommended. They would launch at 6,000 yards.

In deciding this, they not only disregarded the advice of their own ‘experts’, they acted counter to their own best judgements. After the failures of D-Day, key naval figures were quick to claim they had always thought the DD tanks were a hairbrained idea. RADM Hall is perhaps the most notable among this crowd. Yet despite those supposed misgivings, they directed the launching of the ‘unseaworthy’ DD tanks at distances far greater than recommended. Their supposedly strong misgivings were so far at variance with what they directed in their orders that one must doubt whether those misgivings were authentic, or were merely post-debacle attempts to distance themselves from the consequences of their own orders.

The unfortunate fact is that there is no indication as to who was the original father of this decision. The highest level order citing that distance was RADM Kirk’s order for the Western Naval Task Force, however similar guidance was in effect at every beach, whether American, British or Canadian (at the British and Canadian beaches, the launch line was even farther out – 7,000 yards).[3] This would seem to indicate the policy came from Admiral Ramsey or even General Montgomery. Yet there is no record of any such order coming from either man.

There may have been grounds for this 6,000 yard decision. The fear of enemy coastal artillery may have imposed this caution; after all, launching required the LCTs to remain almost stationary, making for an easier target at closer ranges.[4] This possibility is underscored by the fact that at the British and Canadian beaches, instructions were not only to launch the DD tanks at 7,000 yards, but be prepared to launch them from even farther out if under fire from shore batteries.

Nevertheless, the 6,000 yard line stands at the apex of the DD tank fault pyramid, not necessarily because of the degree of the ensuing damage it may have caused, but because it so perfectly illustrates the lack of common sense brought to bear on this matter.

A Cascading Series of Errors

At Omaha, the confusion started with RADM Hall and subsequently infected all lower echelons. It began with Hall’s initial decision for apportioning responsibility. COL Severne MacLaughlin (Commander, 3rd Armored Group, the parent headquarters for both the 741st and 743rd Tank Battalions) reported Hall’s initial plan was for MG Gerow to make the decision if the weather was bad.[5] (Gerow, the V Corps Commander, would be with Hall aboard his command ship the USS Ancon, 23,000 yards offshore in the Transport Area.) In other words, Hall tried to remove himself completely from the matter.

Recognizing this was entirely unsatisfactory, MG Bradley (commanding the First U.S. Army) sent his letter to RADM Kirk, insisting on two points: 1) that the decision be made by the Assault Force Commander, with advice from the Landing Force Commander; and 2) that the decision should not be delegated to individual craft level. Although RADM Kirk changed his order (CTF 122) to allow breaking radio silence prior to H-Hour to facilitate such a decision, Hall rejected the idea in his own order. As far as can be determined, no answer on the record was provided in response to Bradley’s letter, and there is scanty and conflicting documentation on Hall’s decision on the matter before 6 June 1944.

In the wake of the confusion of responsibility on D-Day, Hall belatedly penned an apologia in his 22 September endorsement of Rockwell’s report. In it he attempted to show that he had provided clear guidance on the launch-or-land decision.

“2. The question as to who should decide whether to launch DD tanks was discussed at length by the Assault Force Commander with the Commanding General, Fifth Corps, U.S. Army and the Commanding General, First Infantry Division, U.S. Army. For the following reasons it was agreed that the decision should be left to the Senior Army Officer and the Senior Naval Officer of each of the two LCT units carrying DD Tanks:

“(a) They had more experience than any other officers in the Assault Force in swimming off DD Tanks from LCTs.

“(b) The decision should be made by someone actually on the spot where the launching was to take place and embarked on an LCT rather than on a large vessel. A decision under such conditions should be sounder than one made on a large vessel miles away where the sea conditions might have been much different.

“(c) If a decision were to be made elsewhere and action had to await an order, confusion and delay might result in the absence of such an order, and it was anticipated that communications might be disrupted by the enemy action so that it would be impossible to transmits orders by radio.

“NOTE: The two unit commanders were to inform each other by radio of the decision reached.”[6]

It is impossible to miss the unintended irony in the concluding note, given the fear of enemy jamming in the preceding paragraph.

In military vernacular, ‘discussed at length’ is usually a euphemism for ‘there were strong and irreconcilable disagreements.’ Similarly, in that context, the phrase ‘it was agreed’ generally means the commander made a decision over objections of key subordinates, who ultimately had to go along with the boss’ decision. Despite the false patina of unanimity, that paragraph indicates opinions were sharply divided.

The reasons Hall laid out for his decision did have the virtue of having some merit and might have been convincing were it not for his original stance. In that original stance, he would have had Gerow making the decision under the identical ‘limiting’ circumstances (23,000 yards offshore aboard a large and stable ship), and Hall was just fine with that. But after Bradley’s letter of protest, the decision was kicked back to Hall, and suddenly the conditions that Hall thought were fine for Gerow’s decision-making, were now completely unacceptable if Hall himself had to make the decision. This cast the rationale listed in Hall’s apologia in their true light: they were not put forward as sound tactical considerations, they were merely convenient pretexts that would enable Hall to again avoid responsibility in the matter. In Hall’s revised analysis, such a decision could only be made by a man ‘on the spot’ in the boat lanes with expertise in the matter of DD tank launchings, which, not so coincidentally, ruled himself out.

From this, I believe Hall’s primary motivation clearly was to avoid any personal responsibility for the decision to launch the ‘gimmicks’ in which he had no faith. And this ‘hands off and eyes shut’ attitude was the fountainhead for the confusion of responsibilities that permeated planning and execution. In a cruel twist of fate, Hall’s doubts became self-fulfilling prophesies, because he shunned his responsibilities.

But even if Hall’s assertion that the decision should be made by the man on the spot has merit, that would not justify delegating the decision as far down as eventually happened. At the British beaches, the decision was delegated only down to their equivalent of the Deputy Assault Group Commanders. Recall that Hall’s two Deputy Assault Group Commanders were naval captains (equivalent to Army colonels), both of whom would meet the DD/LCTs at Point K and escort them to the 6,000 yard line for deployment. In other words, they, too, would have been ‘on the spot’ if a decision needed to be made. That would have been the far better solution.

In addition, any validity to his rationale faded to nothing in light of two subsequent events. First was the landing at Utah Beach, where RADM Moon made the launch decision with MG Collins’ advice, and where the Deputy Assault Group commander was on the spot in the boat lanes to issue orders to adjust when the DD/LCTs arrived late. Second, the assumption that very junior officers with six weeks training on DD tanks were the best men to make the decision proved patently unwise. This was an especially risky option as their decision would determine the fate of a critical slice of combat power, upon which so much of the first waves’ success depended.

Hall’s judgement was seriously faulty.

But the question remains, was this truly the guidance Hall issued before the operation? It certainly was never reduced to writing in his own order, nor was it reflected in any of the Army orders. Was this merely Hall revising history to avoid accountability? MacLaughlin once again comes to our aid. His after action report stated Hall and Gerow came to an agreement that:

“ . . . the senior naval commander in each flotilla carrying DD tanks make the decision as to whether the DDs would be launched, or the LCTs beached and the tanks unloaded on the shore. The senior DD tank unit commander was to advise the flotilla commander in this matter.”[7]

While generally in line with Hall’s version, there was a significant difference. Where Hall described a joint decision, with the Army responsibility emphasized by being mentioned first, MacLaughlin’s version clearly indicated it was a Navy decision, with Army input (paralleling, in part, Bradley’s position). Thus, from this initial decision, the Navy and Army were not on the same page regarding this key responsibility. Such is usually the case when contentious matters are decided without being documented or translated into orders.

And apparently, not all the actors within the Navy were on the same page, either, and this failure was also a result of Hall’s faulty planning. Neither Hall’s original operation plan (dtd 23 May 1944) or its subsequent change (30 May 1944) mentioned such a decision would be a joint Army-Navy responsibility. His original order merely instructed two of his Assault Group commanders that the DD tanks might have to be landed, and left unstated who would decide. In the absence of guidance from above, the orders of the two assault groups were naturally disjointed. The Assault Group O-1 order did mention the decision would be a joint Navy-Army responsibility, but only mentioned it in a footnote to an annex detailing the employment of Landing Craf, Support (Small). The order for Assault Group O-2 didn’t address the topic at all. Further, by the time Hall’s order and the two assault group orders were issued, the DD/LCT teams had been broken up, with the LCTs and their embarked DD tanks already sailed for Portland, and the tankers already shipped off separately to the final marshalling areas. If either the Assault Group Commanders or their deputies had any additional role in clarifying or coordinating the matter (most critically with the sequestered tankers) it was not recorded.

The final act in this confusion occurred just a day or two prior to the initial sortie, when the tankers rejoined the LCTs in Portland Harbor. This was when Rockwell decided that instead of the decision being made separately within “each of the two LCT units carrying DD Tanks,” he would insist on one Army officer making the decision for both LCT units. Although he didn’t mention what role, if any, he would have in this proposed change, it was clear he was attempting to override both Hall’s agreement with the Gerow and the Assault Group O-1 order. Whatever Rockwell hoped to achieve, his actual result was to introduce more confusion. Barry, leading the DD/LCTs of Assault Group O-1, understood that the decision reached at that meeting placed the decision authority solely in the hand of the Army. Both his Army counterpart (CPT Thornton) and his own OiCs operated on D-Day consistent with that belief. For that matter, Rockwell’s oral history indicated he and Cpt Elder did as well.[8] All of this ran completely opposite to the version Rockwell penned after the landing.

Rockwell also had a hand in the cascading embarkation errors. While he was not solely responsible for the disconnect between the embarkation scheme and subsequent sailing instructions in Assault Group O-1, it’s clear he conducted embarkation with inadequate information. This was compounded by failing to anticipate how the changed sailing instructions would impact the placement of Barry within the formation he commanded. This then led to the last-minute switch between the OiCs of two LCTs, which in turn led to Barry and Thornton being physically separated (during a period of radio silence), and indirectly led to the new OiC in Thornton’s craft getting lost in the boat lanes. . . . which in turn, forced Thornton to make a decision while separated from three quarters of his command. Every error compounded the effects of the previous error and all conspired against sound decision-making in the DD/LCTs of Assault Group O-1.

Rockwell was more directly responsible for the error which saw Companies B and C of Assault Group O-2 being loaded on the wrong LCT sections. While this did not seem to affect the outcome within his own division on D-Day, it was another distraction that had to be managed as he was dealing with other problems just before the sortie.

Barry and Thornton do not escape responsibility, though it is abundantly clear their share of the blame is far, far less than Hall, Rockwell and history have heaped on them. Objectively, Thornton made the wrong decision. Were there mitigating considerations? Yes. Reports of the state of sea and wind varied widely among observers, and to make an Army officer responsible for a decision based on his judgement of sea state is simple folly. Yet he was stuck with that decision, and he made the wrong one. It appears to have been an honest mistake, but mistake it was. The bottom line, however, was that his error was just the last one of an unbroken series of errors that started with Assault Force Commander, and which could only result in disaster of one sort or another.

Barry’s responsibility is far more difficult to assess. He was largely a victim of Rockwell’s poor decisions regarding chain of command, formations and placement of Barry within that formation. As a result of Rockwell’s belated recognition of his own error, Barry set off on 5 June in an unfamiliar craft, with an unfamiliar crew, in charge of a formation three quarters of which were not from his normal flotilla, group or section. Worse, Barry’s understanding of the outcome of Rockwell’s agreement on who would make the decision to land would place him in the precise position – with no role in the decision – for which Hall would later excoriate him.

One other category of responsibility must be noted. This involves the two Deputy Assault Group Commanders (CAPT Imlay and CAPT Wright). Theirs are errors of omission, not commission. While they both noted how bad the sea conditions were, neither took the initiative to intervene. It’s hard to put all the blame on a junior officer’s decision, when older, wiser heads with more braid on their visors stood by and failed to act. The blame here is somewhat worse for CAPT Wright, who, instead of leading the DD/LCTs to the 6,000 yard line, had CAPT Sabin take that role while he went back to the Transport Area to tend to his LSTs.

Also falling into this category are various Army officers. MacLaughlin was involved from the outset in the contentious matter of who would make the decision, and while he clearly knew how important it was, he failed to monitor the developing plans and ad hoc decisions – at least there is no record of him objecting as the process continually went awry. He can be partially excused as he apparently was aboard the USS Ancon and not present when Rockwell held his pre-sortie meeting with the Army battalion commanders. Assessing the role of the two tank battalion commanders is difficult without knowing how much of the internal Navy confusion they were aware of, whether they were aware of Bradley’s position or whether they knew of Hall’s agreement with Gerow. The tank battalions’ own orders had been issued before those of the two naval Assault Groups—which, in any case these units may not have received—so could not incorporate any of the (sparse) guidance the naval orders included. Beyond that, without a reliable, independent source for what took place in Rockwell’s pre-sortie meeting, there is no way to know whether their role in that meeting was constructive or added to the confusion. The only judgement that can be rendered here is a very general observation that they did not impart a strong enough sense of caution on their company commanders. Even this limited observation really only applies to LTC Skaggs of the 741st Tanks Battalion and is tempered by the fact that Skaggs’ version of events has never been put on the record (despite his offer to provide it to Cornelius Ryan).

And of course, the Army chain of command—from the 16th Regimental Combat Team through the 1st Infantry Division to the Vth Corps—can be similarly faulted for not paying enough attention to this critical matter. As early as December 1943, Gerow voiced his doubts at a conference on Overlord:

“I don’t know whether it has been demonstrated or not: what will happen to those DD tanks with a three- or four knot current? . . . I question our capability of getting them in with that current and navigation.”[9]

Having such doubts so early in the process, one can fault Gerow (and probably others) for failing to watch more closely the evolving plans for employing the DD tanks. These were errors of omission, but did fall directly within a commander’s explicit responsibility for supervision.

The most unconscionable part of this tragedy took place in the days, weeks and even months after 6 June, when individuals were seeking to avoid blame. Rockwell’s actions come in for the most severe criticism, if for no other reason than short-stopping the reports of the LCT OiCs. He misrepresented the comments of the OiCs to the benefit of his version of events. Worse, he wrote his own action report before he even received two of the OiC reports, one notably being Barry’s. That meant Rockwell condemned Barry without even considering his account. And the fact that Barry’s account directly contradicted Rockwell on the most vital point casts Rockwell in an even worse light, from which one might logically infer he did that intentionally to keep the potentially embarrassing facts of the matter buried.

Rockwell’s hypocrisy was further emphasized with his decades-later admission that within his own division, they had indeed launched “one or two” DD tanks that promptly sank. This revealed that Rockwell’s judgement was also so poor that he allowed launching in ‘clearly unsuitable’ weather conditions – the same sin for which he condemned his scapegoat, Barry. Again, it is another vital point he seems to have concealed when the hunt for someone to blame was under full swing.

Hall’s endorsement of Rockwell’s report (quoted in part above) was equally as self-serving, and, if not blatantly false in parts, was at the very least ill-informed. Any agreement he may have reached with the V Corps Commander had long since been rendered outdated by sloppy orders or the unsanctioned changes Rockwell instigated just before sortieing. Had Hall been kept in the dark on this? Clearly not, as Rockwell’s report plainly stated the decision had been left to the senior Army officer of each group. Which indicates Hall was trying to spin the facts.

Hall’s endorsement omitted the point that Elder had launched ‘one or two’ tanks without consulting Rockwell (as Rockwell noted in his oral history), which would have revealed that Hall’s joint decision policy had been disobeyed. This is likely because Rockwell concealed that matter from Hall (and from history for 40 years), just as he had withheld Barry’s report. But if Hall had been kept in the dark on this point, it demonstrates the fact that Hall’s inquiry into the matter had been woefully inadequate. So, was Hall uninformed of this? Or did he know and simply chose to omit it? This is crucial, as up to that point, the Rockwell/Elder team had functioned exactly as the Barry/Thornton team had, the only difference being Rockwell/Elder took action to stop the mistake before it became total. This distinction was lost on Hall, and as a result his endorsement drew a comparative picture that was false and prejudicial to Barry and Thornton.

And finally, Hall’s bland assertion that the Army and Navy leaders were supposed to consult by radio is undermined by his order that did not grant them authority to break radio silence. Rockwell’s oral history made it clear that when Elder and he broke radio silence, it was in violation of orders. (Although the tank radio nets were authorized to be opened at 0500 hours Rockwell’s report and oral history both indicate he was not aware of that, and there is no indication Hall was, either.) Again, Hall’s endorsement painted a picture that was not an accurate reflection of the operational conditions Hall himself had set.

A close examination of Hall’s endorsement raises more red flags. It was written three and a half months after D-Day and fully two months after Leide’s endorsement to the same Rockwell report. A quick survey of 43 endorsements which Hall provided to the reports of subordinate units or ships, shows 37 had been issued by 15 August, with the vast majority signed within a month of receipt. The last endorsement signed was on 22 September, and not coincidentally that was the endorsement to the very questionable Rockwell report. Clearly, he had been sitting on that contentious matter for as long as possible (which should also have given him time for a thorough investigation into the matter – something he did not do). By that date, the 741st Tank Battalion was no longer attached to the 1st Division, having been attached to a second and then a third division, and many of the key Army figures in both battalions were killed or evacuated from theater due to wounds. Not that it mattered much, because Hall did not provide distribution of his endorsement or Rockwell’s report to the 741st Tank Battalion (busy racing through France at the time), effectively blindsiding the tankers. Of the four Army units he did include in distribution: Bradley no longer commanded the First US Army, Gerow no longer commanded V Corps (having been recall to testify before the Army’s board investigating Pearl Harbor), the 1st Division hadn’t seen the 741st in more than 3 months, and the 743rd Tank Battalion was also under a new commander. Further, in the distribution block to his endorsement, Hall excluded the basic letter (Rockwell’s report) from delivery to the 743rd Tank Battalion. Between this act and completely omitting distribution to the 741st Tank Battalion, Hall ensured no one on the Army side who was present at Rockwell’s pre-sortie meeting or aboard the LCTs on D-Day could read and dispute Rockwell’s questionable version of events. He was just as sneaky on the Navy side; he did not forward any of these documents to LCT Flotilla 19 – the unit Barry belonged to (though he did provide a copy to Rockwell’s and Leide’s Flotilla 12).

Hall’s handling the of the affair’s aftermath is perhaps the classic ‘indictment-by-endorsement’ bureaucratic maneuver, wherein a potentially embarrassing investigation is forestalled by a carefully spun story that closes out an affair by shifting the blame to someone not in a position to defend himself. Nothing else captures the essence of the DD tank saga as does this sorry concluding action.

But that isn’t the end of Hall’s role in the matter. In a further paragraph of his endorsement to Rockwell’s report he betrayed an utter lack of understanding for the ground combat side of such assaults.

“(b) That under normal circumstances, artillery, tanks and other armored vehicles, which have to be transported in large landing craft, should not be landed in an assault until the beach has been cleared of enemy resistance and the vehicles and craft carrying them will not be exposed to direct aimed artillery fire during the landing.

“(c) That if circumstances make it necessary to employ tanks, artillery or other armored vehicles in the first wave or other early waves of the assault, they have a far better chance of reaching the shore in safety if they are transported by landing craft instead of swimming in under their own power.”

“Under normal circumstances . . . “ is a bizarrely inappropriate phrase to lead a recommendation about an assault so spectacularly un-normal as Omaha Beach. If followed, Hall’s recommendation was tantamount to throwing unsupported infantry ashore reminiscent of the WWI mass attacks, and it disregarded everything learned about the essential need for combined arms operations, even at the earliest stages of an assault. In his formal report on the landings, he expanded on this point, suggesting that naval gunfire was all that the assaulting troops would need for support. Spoken like the old Battleship sailor he was. Yet this completely disregarded the massive failures of bombardment in his own landing – largely due to communications breakdowns between ships and troops ashore. And while the destroyers proved invaluable on D-Day, nevertheless there were numerous enemy guns sited in such a manner that they were impervious to naval gunfire and were only knocked out by tanks ashore. Finally, the lack of adequate bombardment ships and lack of adequate time for such a bombardment in the European Theater precluded giving Hall’s recommendation any serious consideration.

As for the second paragraph, the obvious counterpoint is that one of the two principle reasons the DD tank concept was adopted in the first place was because amphibious commanders, such as Hall, did not want to risk LCTs in the first wave. The whole fiasco could have been avoided had he simply ordered tanks be landed in the first place. But he did not do that. His comments here—lightly cloaking criticism of the Army DD tank concept—are actually the observations of a man who was not self-aware enough to realize he was part of the very problem that generated use of the DDs in the first place.

Other Beaches - Other Results

Utah Beach

Earlier in this installment I touched on Utah Beach. Let’s look more closely at the actions there: how did Rear Admiral Moon handle the same situation over on his beach?

Recall that Moon had no previous amphibious experience, and worse, he had much less time to organize his command and plan for the landings due to the late addition of Utah Beach. It’s no surprise that his force did not come off well in Exercise Tiger (the final Utah Beach rehearsal exercise). And yet, his handling of the DD tank matter on D-Day was far superior to the far more experienced RADM Hall.

Moon decided to keep the question of launching DD tanks in his own hands. He did not delegate it. While this may not have been the best echelon for that decision, it was at least a clear assignment of responsibility, something lacking in Hall’s command. Second, he would seek the advice of his Army counterpart, MG Lawton Collins (the VII Corps commander, riding in Moon’s command ship), ensuring unanimity of command. These two provisions alone eliminated the wide array of problems that arose in Hall’s command.

The result was a much different mentality on D-Day, with executing units knowing where to look for a firm decision. This began at the bottom, with USCG Cutter 17 flagging down the commander of CTG 125.5 (Commander E. W. Wilson) at 0309 hours to ask whether the DD tanks were to be launched or landed. Wilson then proceeded in his flagship (LCH-10) to the USS Bayfield (the Utah command ship) and put the question to Moon. Moon consulted with Collins at 0333 hours and the two decided to go ahead with the launching. It was a clear decision made in a timely fashion and quickly passed to all the necessary parties.

DD Tanks on the Beach at Utah.

Life, however, is not that simple. The DD/LCTs were not yet on hand to launch the tanks. The convoys carrying the Utah landing force encountered the same problems in crossing the English Channel as did the Omaha convoys. In this case, the DD/LCTs were running late. Fortunately, Wilson was on top of matters and anticipating problems. At 0347 hours, he queried the Bayfield, “If LCTs do not arrive for first wave, do you want to hold LCVPs?” At 0353 hours he was told, “Do not wait for LCTs with DD tanks.” He passed that word on at 0400, adding he would send the DD/LCTs when they arrived. At 0426 hours the DD/LCTs arrived and were sent in.[10] In an effort to catch up with the assault waves, the DD/LCTs passed the 6,000 yard line, closing to 3,000 yards where they launched their tanks. The DDs crawled ashore roughly 10 minutes after the first wave (i.e, 20 minutes late). [11]

The relative lack of beach defense at Utah might give the mistaken impression that all went well with the landing. It did not. But at least when it came to the DD/LCTs, the command responsibilities, planning and leadership resulted in sound execution, even in light of the late arrival of the convoy.

The Eastern Naval Task Force

The operation orders for the British and Canadian assault forces called for the DD tanks to be launched at an even greater distance—7,000 yards—with at least one order warning that in the case of enemy fire, they might have to launch beyond even that. Fortunately, most of their DD tanks were taken into the shore, and those that were launched did so at either 5,000 yards (comparable to the distance at Omaha) or at about 1,500 yards. In all cases, the decision was made by a naval officer with the rank of either captain or commander (equivalent to Army colonels or lieutenant colonels), which was a significant difference from the practice in Hall’s assault force. In almost every case, the decision was made after consulting with the Army counterpart.

The employment of DD tanks on the British and Canadian beaches was summarized by Rear Admiral Phillip Vian, the Naval Commander of the Eastern Task Force (under whom the Assault Forces S, J and G operated).

“Launching of D.D. Tanks

“27. The weather conditions were on the border line for swimming D.D. Tanks; in all the assaults the D.D. Tanks arrived late, and after the first landing craft had touched down.

“28. In SWORD Area it was decided to launch the D.D. Tanks but to bring them in to 5,000 yards before launching, in view of the weather and lack of enemy opposition. Thirty-four of the 40 tanks embarked were successfully launched and 31 reached the beach. The leading tanks touched down about 12 minutes late and after the L.C.T. (AVRE). At least one tank was run down and sunk by an L.C.T. (AVRE) and it is credible that not more were hit by these L.C.T. which had to pass through them. Twenty-three tanks in this area survived the beach battle and did good work in destroying strong points which, being sited to enfilade the beaches, presented no vulnerable aperture or embrasure to seaward.

“29. On the JUNO front it was decided not to launch the D.D. Tanks but to beach their L.C.T. with the L.C.T. (AVRE). This was successfully accomplished in Assault Group J.2, but in Assault Group J.1 the D.S.O.A.G. in charge of the L.C.T., when about 1,500 yards from the beach, decided to launch the D.D. Tanks. This resulted in some confusion in the groups following, but all L.C.T. except one launched their tanks, which arrived about 15 minutes late and 6 minutes after the assaulting infantry.

“30. In GOLD area D.D. Tanks were not launched and L.C.T. were beached just after the L.C.T. (AVRE).” [12]

Interestingly, he described the conditions as “on the borderline for launching D.D. Tanks”, which to some degree parallels the mixed observation of the conditions in the Omaha Assault Area. The far happier results of the 34 DD tanks launched at Sword Beach, which were launched at a distance nearly the same as at Omaha, indicates the sea conditions there were actually more moderate than at Omaha.

Of course, few sources agree as to the actual losses among DD tanks, and some disagree even whether units were launched or landed. For instance, at Gold Beach, where RADM Vian reported all DD tanks were landed on the beach, one source stated 32 DD tanks of the Nottinghamshire (Sherwood Rangers) Yeomanry were launched inside of 700 yards, and only 24 made it in. Similarly, yet another report stated that of the 38 DD tanks of Group J.1 that launched close inshore at Juno Beach, 19 foundered. Most of these discrepancies can be accounted for due to the fact that a substantial number of DD tanks were drowned out in the surf after touching down. In some cases, there was water inside the canvas screen that the pumps could not handle, and when the tank’s front pitched up with the gradient of the beach, the water flooded to the rear and into the engine compartment. In other cases, incoming waves broke over the back of the deflated canvas skirts and flooded the engine compartments. These cases cannot be counted among those that foundered while swimming, and regardless, in most of these cases, the crews continued to fight their disabled tanks until the tide reached inside the turrets.

A DD tank mired in soft ground at Gold Beach.

To my mind, the example of the British and Canadian beaches—as well as Utah Beach—provided the cautionary lesson that proper employment of an operationally fragile system in a questionably suitable environment requires the judgement of seasoned and mature officers of appropriate rank and of the appropriate armed service. The failure to recognize this truism was a major factor in fathering the debacle of the 741st Tank Battalion.

Parting Comments

And with that we conclude this deep—very deep—dive into the circumstances surrounding the employment of Duplex Drive tanks at Omaha Beach. The subject turned out to be vastly more complex than I anticipated, requiring no fewer than six long installments to do it justice. Even at that length, I saw fit to omit discussion on some points, such as the possible effect stronger-than-anticipated currents might have had on collapsing the screens as the swimming tanks tried to steer ‘upstream’ to counteract their drift to the east. I also omitted discussion of the actions of the surviving tanks once they made it ashore – a subject covered many times by many authors, and not within the focus of my series.

Incomplete as this series may be in those respects, I’m confident this has been the most thorough treatment of the subject, revealing several layers which have not been told elsewhere.

When I first set out to review the impact of the planning process and the orders for Omaha Beach, I intended not to make this a witch hunt or an attack on individuals. I wanted to focus on systems and processes, doctrine and planning. Unfortunately, the sheer scope of errors, bad decisions, sloppy plans and shabby cover-ups called for more sharply focused conclusions where some individuals were concerned. I regret having to do it, but not having done it.

In future posts, I will continue to explore how strategic priorities, resource constraints, command decisions and the planning system affected the conduct of operations at Omaha Beach. I hope you’ll join me.

[1] As most of the documents referenced in this installment have been thoroughly discussed and cited in previous installments, I will omit duplicating them here, and will only include citations for newly introduced documents.

[2] In the original design a canvas curtain had walled off the area above the engine compartment. This was replaced by a chimney-like exhaust stack which may have addressed the carbon monoxide poisoning threat, but that isn’t clear in Duncan’s report.

[3] For Juno Beach see ONEAST/J.2, Appendix C, para 2(c), pg 689; for Sword Beach, see ONEAST/S.7b para 12, pg 994; for Gold Beach, see ONEAST/G.FOUR, Part II, para 8, pg 1346; for. All three orders are contained in Allied Naval Commander-in-Chief, Expeditionary Force’s complied Operation Neptune Naval Operations Orders which can be found at NARA RG 38 or online here. Page numbers cited here refer to those of the online file.

[4] At one British beach, instructions were to actually anchor during launching.

[5] Commander, 3rd Armored Group, Report After Action Against Enemy, June 1944, pp 2-3. NARA, RG 407, Box13647, Entry 427.

[6] Commander, Assault Force “O” 22 September 1944 second endorsement to Com.Grp 35, LCT (6) Flot letter of 14 July 1944. NARA, RG 38 or online here.

[7] MacLaughlin, op cit.

[8] In that oral history, the revelation that one or two tanks were launched as planned without Rockwell giving instruction – they had not yet broken radio silence – indicates he had no role in the decision-making.

[9] Balkoski, Joseph. Omaha Beach: D-Day, June 6, 1944 (p. 98). Stackpole Books. Kindle Edition.

[10] CTG 125.5 (Commander, Red Assault Group), Action Report, Operation Order N0. 3-44 of Assault Force “U”, Western Naval Task Force, Allied Naval Expeditionary Force, dtd 12 July 1944, encl 1, pg 1. NARA RG 38, or online here.

[11] CTF 122 (Commander, Western Naval Task Force), Operation Neptune – Report of Naval Commander, Western Task Force (WNTF), pg 163 (online page reference). NARA: RG 38, or online here.

See also: CTF 125 (Commander, Force “U’), Report of Operation Neptune, dtd 26 June 1944, pg 654 (as contained Report of the Allied Naval Commander-in-Chief Expeditionary Force on Operation Neptune, dtd 16 Oct 1944). NARA 38, or online here.

[12] Operation Neptune – Report of Naval Commander Eastern Task Force, dtd 21 August 1944. Vian’s report is in Volume II of the Report of the Allied Naval Commander-in-Chief Expeditionary Force on Operation Neptune, dtd 16 Oct 1944. Vian’s report begins at pg. 178. The reports of his subordinate force commanders are also contained in that same document as follows: Force S Commander, pg 241; Force G Commander, pg. 330; and Force J Commander, pg. 439. This document can be found at NARA, RG 38, or online here.

The Duplex Drive Tanks of Omaha Beach, Part (e) Success at the Dog Beaches

This installment follows the DD tanks of the 743rd Tank Battalion, which were scheduled to land on the western half of Omaha Beach. These tanks belonged to Company B (CPT Charles W. Ehmke) and Company C (CPT Ned S. Elder) and were embarked in eight LCTs under the command of Lt.(jg) Dean Rockwell, USNR. In contrast to the debacle on the eastern half of Omaha Beach, the popular story of the landing of the 743rd’s tanks was one of complete success, due primarily to the excellent judgement and resolve of Lt.(jg) Rockwell - and maybe CPT Elder, too, depending on which story you read.

This installment digs into the facts behind that popular story, relying on Rockwell’s little known 1990 oral history which revealed a key element of the popular story was not entirely true. It also includes a never-before-published photo taken of a knocked out DD tank on Dog White beach sector.

The Price of a Beachhead. Knocked out Duplex Drive tank of the 743rd Tank Battalion and casualties from the 29th Infantry Division, astride the seawall near the boundary of Dog Green and Dog White. This never-before-published photo was taken by Tech/3 Burton Hartman, Detachment Q, 165th Signal Photo Company, and is used here with the permission of his son, Barry. It’s believed to have been taken early D+2. (Copyright protected, use without the permission of Barry Harman is forbidden)

Introduction

In the previous installment (The Duplex Drive Tanks of Omaha Beach, Part (d) The Debacle Off Easy Red and Fox Green) we followed the story of the DD tanks of Army Captains (CPT) James Thornton and Charles Young, and the Landing Craft (Tanks) (LCTs) of Lieutenant (junior grade) (Lt.(jg)) Barry that carried them to the eastern half Omaha Beach. That account focused on the series of bad decisions, poor planning and mistakes in execution that culminated in 27 of the 32 DD tanks sinking before reaching the beach. This installment follows the DD tanks of the 743rd Tank Battalion, which were scheduled to land on the western half of Omaha Beach. These tanks belonged to Company B (CPT Charles W. Ehmke) and Company C (CPT Ned S. Elder) and were embarked in eight LCTs under the command of Lt.(jg) Dean Rockwell, USNR.

In contrast to the debacle on the eastern half of Omaha Beach, the popular story of the landing of the 743rd’s tanks was one of complete success, due primarily to the excellent judgement and resolve of Lt.(jg) Rockwell - and maybe CPT Elder, too, depending on which story you read.[1] Those versions of events might possibly have been influenced by the fact that the only source for them was Rockwell himself. Neither of the Army company commanders survived long enough to bear witness to what happened that day. Captain Ehmke was killed soon after his treads met sand on D-Day. Captain Elder was killed in action on 14 July (coincidently, the same day Rockwell submitted his report on the landings). The confusion resulting from the intense combat and casualties during the landings resulted in the battalion’s documentation of the day being rather incomplete.

So, the story of the battalion’s landing has been almost completely dominated by Rockwell’s contemporary official report and Read Admiral (RADM) Hall’s self-serving endorsement letter. That is, until a new narrative appeared in the early 1990s which called a significant aspect of the ‘official’ account into question. Unfortunately, this new narrative had extremely limited exposure, which is a shame, since it, too, came from the pen of the former Lt.(jg) Dean Rockwell.

Sortie and Crossing

As discussed in the previous installment, the initial 4 June sortie had been halted and turned around due to an unfavorable weather forecast for 5 June, the original invasion date. The false start helped the DD/LCT force as it permitted hasty repairs to some ramp gear that had been damaged in the initial sortie, as well as replacing one LCT engine.

The false start had also demonstrated to Rockwell that the revised sailing formation had placed Lt.(jg) Barry in a position from which it was impossible to control the eight LCTs in his division.[2] Less than 3 hours prior to the second sortie, Rockwell switched the officers in charge (OICs) of two LCTs, placing Barry at the lead of his force.[3] It was good decision, but made far too late, and was to add to the confusion in that division on D-Day.

Rockwell was spared that confusion within his own division. Unlike Barry (who was assigned as the OIC of LCT-537) Rockwell was the commander of an LCT group and was not the OIC of a vessel. To cope with the new sailing formation, he could shift his flag from craft to craft without disrupting the internal chain of command of his LCTs

During the crossing of the English Channel, Rockwell exercised command over all 16 of the DD/LCTs headed for Omaha Beach, to include Barry’s division. During this second sortie, the DD/LCTs encountered additional confusion caused by the Utah Beach convoys that hadn’t had time to return to their ports of origin and had taken shelter in Weymouth Bay. It was chaotic, to put it mildly. When dawn came, the mass of shipping began to try to shake itself out into some semblance of order. Due to a shortage of minesweeping flotillas and time in which they could operate, the convoy lanes were narrow and the convoys themselves became intermixed and partially disrupted by smaller towed craft that had broken free of their tows. Amid this mess, Rockwell realized he’d lost one LCT. After searching for it for most of the morning, he found his lost LCT-713 sailing in a nearby convoy headed for Utah beach, and he ushered it back into formation. Perhaps it was no surprise. LCT-713 was one of the last craft built and one of the last craft to join the Omaha Beach LCT flotillas; craft and crew were as green as they came. Despite the challenges of heavy weather in the Channel and confused traffic in the convoy lanes, the multitude of ships and craft managed to arrive at the Transport Area anchorage off the Omaha Assault Area, in confused and straggling formations, but or more or less on time.

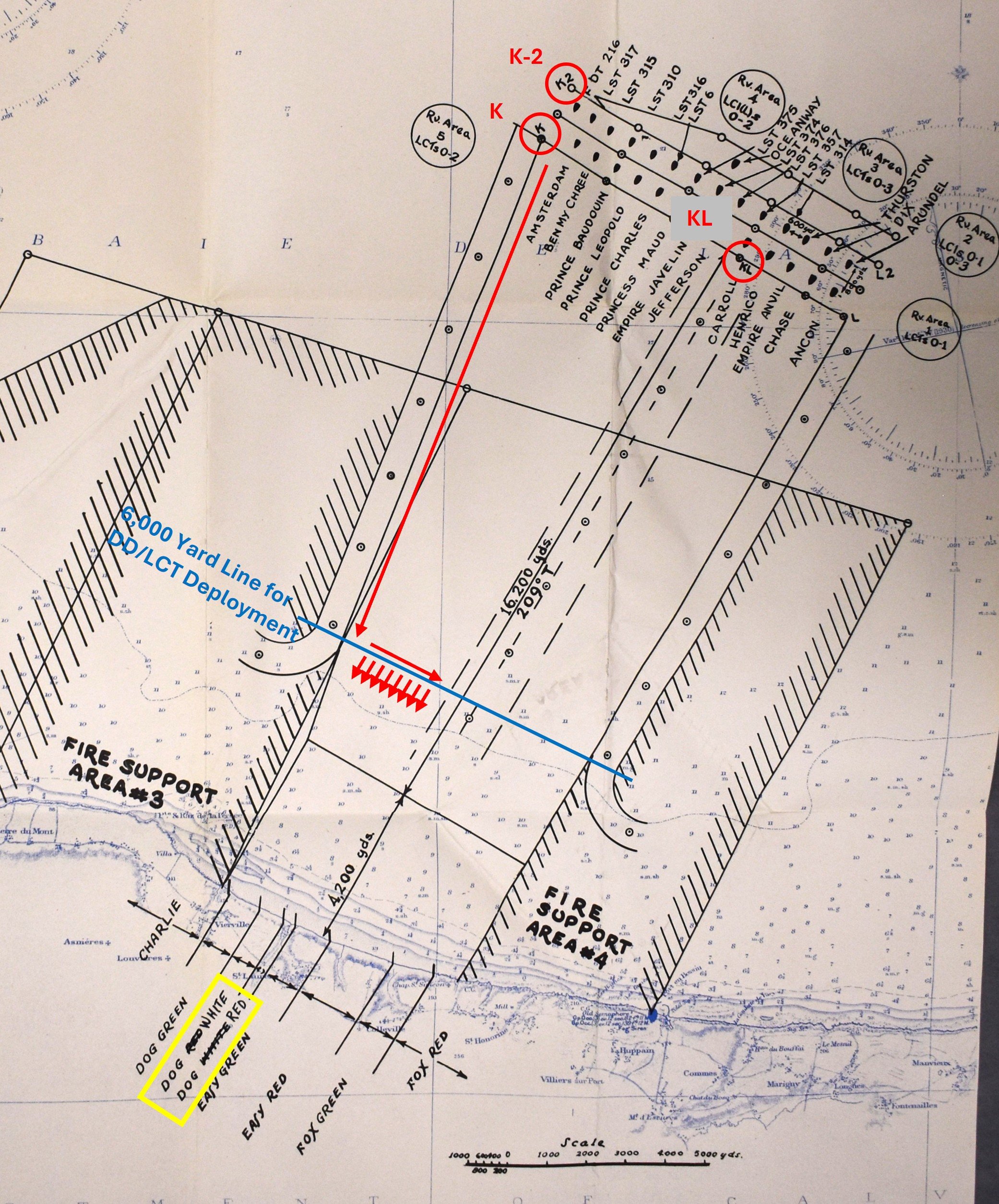

Figure 1. The D-Day Convoy Routes. This chart shows how convoys from all of the invasion points converged at Point Z (ZED) near the Isle of Wight before turning towards the coast of France. Although necessary due to the short time allotted minesweeping, the narrowness of the lanes resulted in jammed and confused traffic.

From Point K to the 6,000 Yard Line

On each flank of the Transport Area (23,000 yards off Omaha Beach) there were rendezvous areas for LCTs; one for the LCTs of Assault Group O-1 and one for those of Assault Group O-2. However, as the DD/LCTs would be first wave, and as they had arrived late, Rockwell brought both his and Barry’s divisions directly to Point K (aka Point King), located at the western limit of the O-2 boat lanes. At that point Barry’s and Rockwell’s divisions were to separate, with Barry’s eight craft continuing eastward to Point K-L (King-Love) on the western flank of the O-1 boat lanes. (See chart).[4]

Point K was an important and busy location early on 6 June. Also due to rendezvous at Point K were: eight Landing Craft (Armored) (LCT(A)) carrying wading tanks and tank dozers; eight Landing Craft, Mechanized (LCM) carrying the gap assault teams for the O-2 beach sectors; three control craft; and 12 landing Craft, Support (Small) (LCS(S)).[5] In addition, two Landing Craft Infantry (LCI), carrying the deputy assault group commanders for O-1 and O-2 would be there to shepherd the first waves into position. Rockwell placed his arrival in the Transport Area at 0345 hours and proceeded to Point K, where, he stated, he was met by LCS(S)s “that were to lead us to the line of departure.”[6] This was not quite accurate.

Lt.(jg) Bucklew, the OIC of the 12 LCS(S)s told a different story. He reported he, too, arrived at Point K at about 0345 hours where he found the DD/LCTs, the LCT(A)s and the LCMs. However, none of his other 11 LCS(S)s had arrived, and the guide craft had already set off down the fire support lane. The LCS(S)s had not made the Channel crossing on their own bottoms, rather were ferried over on the decks of Landing Ships, Tank (LSTs) and attack transports. As these larger ships arrived, they hoisted out the LCS(S)s, who then set out individually or in groups of two or three to find Point K in the dark, with only Bucklew’s craft arriving on time. Neither of the deputy assault group commanders were to be seen.

Bucklew made the command decision to remain at Point K and look for his lost LCS(S)s, and Rockwell made the command decision to proceed down the fire support lane to try to catch up with the guide craft. Each of these turned out to be a correct decision. Bucklew soon located his missing craft and the fast LCS(S)s caught up with the lumbering LCTs, taking station in two columns flanking the DD/LCTs. Rockwell was able to maintain contact with the control craft as he followed them down the fire support channel.

When Rockwell turned right into the fire support channel at Point K to pursue the guide craft, his formation had changed from two columns of four LCTs each into a single column of eight LCTs. It was during this evolution that the break in Barry’s division occurred (as discussed in the previous installment), with LCT-537 and LCT-603 mistakenly following Rockwell down the wrong channel.

As the DD/LCTs proceeded down the lane, the craft went to general quarters and the chains holding the tanks securely to the decks were removed. The tank crews began inflating the skirts and the Navy crew wetted down the canvas skirts with pumps. Once the skirts were inflated, the tankers and sailors could only communicate by shouting over the high canvas sides; not only was radio silence still in effect, but the Navy and Army radios were equipped with crystals that did not permit operation on the same frequencies. With the engines of both the LCTs and tanks running, verbal communication between sailors and soldiers was difficult. Communications between craft had to rely on visual signals, and communications between tank units was impossible – at least until 0500 hours when the tankers were allowed to break radio silence.

Rockwell’s action report provided little detail for this portion of the operation. Fortunately, in the early 1990s, he was contacted by Stephen Ambrose and agreed to tape-record his D-Day experiences. (Ambrose did not conduct the interview, Rockwell simply recorded his story.) Although held in the Eisenhower Center at the University of New Orleans, Rockwell’s oral history has been largely overlooked. Patrick Ungashick located a transcript of this recording (along with a number of associated documents) while researching his book, A Day for Leadership: Business Insights for Today’s Executives and Teams from the D-Day Battle. This transcript provided a bit more in the way of minor details (to include the earlier anecdote about the wayward LCT-713).

Figure 2. Omaha Beach and Surrounding Waters. This is a detail from the Omaha Assault Area Diagram which was contained in the Assault Group O-2/CTG 124.4 operation order. I’ve added colored notes and graphics to highlight items discussed in the article. The red arrows depict Rockwell’s DD/LCT division’s movements.

During the crossing of the Channel, the bombardment force, including two battleships and three cruisers, had overtaken the LCT convoy, and these ships were already anchored in their designated positions in the fire support channels. Ahead of Rockwell in his lane were the older American battleship USS Texas (BB-35) and the British light cruiser HMS Glasgow (pennant number C21). The Texas (Rockwell thought it was the battleship USS Arkansas, which was in the eastern fire support area) was a large ship and it was anchored across the narrow channel. Heavily ladened, shallow-draft, and buffeted by waves and wind, the DD/LCTs found it a challenge to avoid the Texas in the pre-dawn darkness. One of the LCTs lacked the seamanship to get by without scraping paint. The battleship was unfazed, but the LCT’s launching gear was damaged. Rockwell omitted this incident from his official report but included it in his oral history.[7] He didn’t identify the hit-and-run LCT, and none of the reports from his LCT OICs confessed to this accident. The report from LCT-713 (Ens White) did note that on beaching, his ramp extensions were damaged, so it may have been the culprit.[8]

Rockwell’s account makes no mention the Deputy Commander of Assault Group O-2. As you recall from the previous installment, CAPT Imlay, the Deputy Commander for O-1, was supposed to meet Barry’s DD/LCTs at Point K, but did not link up with them until near the 6,000 yard line. CAPT Wright, the Deputy Command for O-2, was also supposed to meet up with Rockwell’s division at Point K, but on arriving he decided it should stop at Point K-2 (a few hundred yards farther offshore) to direct the arriving craft. From there he proceeded to the LST anchorage area to supervise the unloading of the DUKWs. Wright’s normal job was Commander, LST Flotilla 12, and this probably accounted for why he allowed his focus to be diverted from the first waves. He did not proceed inshore to the beaches until 1100 hours. As a result, despite being the deputy assault group commander, he played no role in organizing and dispatching the early waves in the boat lanes.[9]

A senior officer who was present close inshore was CAPT L. S. Sabin, Commander, Gunfire Support Craft (CTG 124.8). Although he did not control Rockwell’s division during the approach to the beach, Sabin did command the convoy in which Rockwell’s DD/LCT group sailed to Point K, and he commanded the gunfire and rocket craft that were supporting Rockwell’s LCTs. He had also sailed down the same fire support channel as Rockwell, shepherding his gun and rocket craft into position just behind the DD/LCTs. As a result, Sabin paid close attention to the DD/LCTs that morning. While stationed close inshore before H-Hour, he reported:

“At least one LCT(DD) was observed to the westward, apparently having gone to Utah by mistake. He was headed back to Omaha, but it was obvious he could not make his position in time.”[10]

Rockwell did not mention this incident, either then or later, nor did any of his OICs admit to it. CAPT Sabin’s report was detailed and appears precise and accurate. It cannot be easily dismissed. Sabin’s observation is supported by Folkestad’s The View from the Turret. Folkestad cited an interview with Harry Hansen, then a lieutenant with the DD tanks of Co. C, 743rd Tank Battalion. Hansen stated during the Channel crossing, his LCT lost power and fell out of the convoy. Eventually the engines were restarted and the lone LCT wandered off course, eventually having to ask instructions from a French fishermen. This was probably the lost DD/LCT Sabin saw.[11] Hansen earned the Distinguished Service Cross, the Silver Star, the Bronze Star, and the French Croix de Guerre (with Palm).[12] And he ended the war as a captain. His account, too, must be taken seriously. Together, their accounts are fairly damaging to the credibility of Rockwell and his OICs, who portrayed the run into the beach as smooth and well organized, with not a hint of lost craft.

Despite these incidents, the column reached a point approximately 5-6000 yards offshore by 0515 hours (according to Rockwell’s official report) then turned left, proceeding parallel to the shore until the craft were opposite their target beaches at 0540 hours, at which time they turned right into line abreast formation facing the beach. There are minor differences when these maneuvers took place. Ensign Gilfert (LCT-590, last in the line of eight LCTs) reported the turns at 0530 hours and 0540 hours. Ensign Cook (LCT-588, fifth in line) reported the turn toward the beach as 0530 hours.

There are two versions of what happened next, and they differ in a key respect. Unfortunately, both versions come from Rockwell. We’ll first examine the version based on his 14 June action report and later consider the version from his oral history.

In his 14 July report on D-Day, Rockwell stated:

“At 0505 this command [referring to himself in the third person] contacted Captain Elder via tank radio and we were in perfect accord that the LCTs carrying the tanks of the 743rd battalion would not launch, but put the tanks directly on the designated beaches. Accordingly, all ships did a 90 degree flanking movement at 0540 and proceeded to the beach with the guide ship – LCT 535 – of this command touching down at 0629. The others all touched within two minutes.”

In addition to specifying the time of the launch-or-land discussion (0505 hours), Rockwell’s account sequenced the decision well before the command to turn right into line abreast to face the beach. Again, there is some disagreement on this timing. Ensign Gilfert (LCT-590) recorded that he got the word they would land the tanks at 0500 hours, and Ens Novotny (LCT-591) received the word at 0505 hours, supporting Rockwell’s time. Ensign Cook (LCT-588) said the Army captain informed him of the change “previous to” the flanking turn (which he placed at 0530 hours). But Ens Dinsmore (LCT-589) stated “It was 0530 when we decided the sea was too rough for the launching of the DD tanks.” Ensign Carey (LCT-586) did not state a time, but recorded, “. . . a short while later, orders came across the Army radio to form a line abreast and all ships land on the beach. This we did.” And Ens Pellegrini (commanding LCT-535, in which Rockwell rode) also gave no time for this decision, but placed it immediately before the turn into line abreast in his sequence of events. (The remaining two OICs, Ens White (LCT-713) and Ens Demao (LCT-587) did not mention when they received word of the change.)

Oddly enough, four of the six OICs (to include the OIC of the craft Rockwell was aboard) reported the decision being made, or their receipt of that decision, between the time the column turned left to parallel the beach, and the right flank turn into line abreast. This would place the decision close to the scheduled launch time for the DD tanks (0535 hours). Only two OICs supported Rockwell’s earlier time. The wording of Dinsmore’s report is especially noteworthy. He didn’t say he received word of the change. He stated: “It was 0530 when we decided the sea was too rough for the launching . . . “ [Emphasis added] That seems to imply the decision was made on his craft, which would also imply CPT Elder was aboard. We don’t know what craft Elder was on, and it’s risky to parse inexact timelines too closely, but this raises a possibility.

I question Rockwell’s assertion that he initiated contact with his Army counterpart. The tankers were authorized to break radio silence at 0500 hours, five minutes before Rockwell and Elder supposedly conversed via the tank radios. So it was likely these radios were used to convey a decision. But, as mentioned before, Rockwell had no physical access to those radios. Al he could do was leave the wheelhouse, walk forward in the well deck until he was next to the lead tank, and shout up the the platoon leader, with snippets of conversation relayed via that platoon leader. But that would rely on Elder first opening the net. It’s far more likely it was Elder who initiated the call when he opened the radio net and he who made contact with Rockwell. Which would imply Elder also raised the decision not to launch, as Dinsmore’s report seemed to say. This might seem to be a minor point, but given how we’ve seen Rockwell’s report was heavily spun to cast himself in a good light, it is important to clarify every point.

In fact, Rockwell was not consistent on the matter of who initiated the call. In his oral history, he gave a different version. In it he stated:

“. . . I was in communication by low power tank radio (even though all communications was forbidden prior to H-hour, the decision to launch or not to launch into the sea was absolutely critical to the success of the Invasion. We broke radio silence. What the hell, by now the Germans were aware what was about to happen) with a Captain Elder, of the 743rd tank battalion. We made the joint decision that it would be insane to launch . . . The next signal to all our craft and to the tank commanders that we would proceed to the beach, which we did. And when our landing craft drove up on the shore, the ramps were dropped and the tanks drove off, with their shrouds down, ready to provide coverage to the infantry units that were to come in behind them.”[13]

[As with all oral history and interview transcripts, the narrative reflects the natural speaking style of the individual, resulting in some odd wording and at times confusing syntax. I have not attempted to ‘clean up’ the text and have quoted them as they were transcribed.]

So, in this later version, Rockwell no longer claimed he initiated the call. This may seem a minor point, but it is important to remember that from the very start, Rockwell believed that the launch-or-land decision should be the sole responsibility of an Army officer. He clearly stated this in his 30 April 1944 report to RADM Hall on the DD tank and LCT training programs.[14] And he reiterated it in the days before the sortie, when he pressed for a single Army officer to decide for both battalions.

Yet he sang a much different tune after the successful landing of the 743rd’s DD tanks. Suddenly he was the man with the expert knowledge, common sense, authority, and responsibility and was acting to forestall disaster. Six years after his muted version in the 1992 oral history, he was back to playing the role of the decisive man at the critical moment. As he stated in a letter to Ambrose on 3 August 1998:

“I’m flattered by the credit you gave me for the part I played. Really, it was only a matter of a good judgement and a little knowledge of seamanship. The sea was too rough for the survival of the D.D. tanks. By tank radio the Army agreed with me. (I was going to take them to the beach even if the Army had disagreed.) As the senior Navy officer afloat directing this portion of the invasion, I had the authority and a responsibility to act.”[15]

This stands in stark contrast to his position before 6 June that he should have no role in such a decision. His later insistence on claiming to be the initiator of that decision—or co-equal in the decision—seems to be a rather crude case of rewriting history.

Figure 3. Deciphering Directions. Maneuver terms may be hard to visualize for those not familiar with military matters. This picture shows how Rockwell’s division of LCTs changed formations from Point K to the beach.

The Run into the Beach

After turning right into line abreast and facing the beach, the DD/LCTs could not immediately drive ahead. They had reached the 6,000 yard launch line early, early enough to allow the slow-swimming DD tanks to reach the shore at their scheduled H-10 minutes. But with the decision to land, adjustments had to be made. Since the LCTs were faster than the DD tanks, they had to slow their approach to avoid beaching too early, especially since in a landing scenario, they were supposed to beach 10 minutes later, alongside the LCT(A)s at H-Hour. Ideally, this would put 32 DD tanks, 16 standard wading tanks and 8 tank dozers on the beach almost simultaneously. So, Rockwell’s DD/LCTs initially ambled along, hoping the LCT(A)s of the next wave would catch up by H-Hour.

In Ambrose’s book D-Day, June 6, 1944: The Climactic Battle of World War II, the author’s dramatic narrative described Rockwell’s run to the beach in these terms:

“Further, the smoke obscured Rockwell’s landmarks. But a shift of the wind rolled back the smoke for a moment and Rockwell saw he was being set to the east by the tide. He changed course to starboard and increased speed; the other skippers saw this move and did the same. At the moment the naval barrage lifted, Rockwell’s little group was exactly opposite Dog White and Dog Green, the tanks firing furiously.”[16]

Aside from the obvious error (the DD tanks could not fire over the ramps of their LCT; Ambrose confused the DD/LCTS and the LCT(A)s), something is amiss here. None of Rockwell’s correspondence with Ambrose mentions anything written in that paragraph. Instead, Ambrose seems to have taken the experiences of another man and portrayed them as Rockwell’s—right down to the use of the nautical term ‘set’ for current direction—with some modifications to enhance Rockwell’s image . That man turns out to be Lt.(jg) Bucklew, whose LCS(S)s led Rockwell’s division from the 6,000 yard line to the beach, with one LCS(S) preceding each LCT to guide and to provide suppressive fires with rockets and machine guns. And it was Bucklew who was responsible for navigation during that phase. Bucklew’s account had this to say.

“4. . . . The LCT’s and LCS(S)’s then ran at slow speed to allow the LCT(A)’s of the first wave to catch up. Beach objects and Control Vessels were now visible, and the ascertaining of our position was now assured.

“5. Upon crossing the line of departure, beaching formation was taken by the LCT’s and LCT(A)’s, with LCS(S)’s slightly ahead and guiding them in. When about 2000 yards off shore, beach identification showed that the group was being set to the left. Course was changed to remedy this and speed increased to maximum to allow beaching on time.

“6. When about 400 yards out, directed two rockets to be fired as ranging shots. On observing them explode in the Target Area, all LCS(S)’s opened fire, firing quick salvos and maintaining a continuous fire for about five minutes. By continuously advising the leader of the LCT’s (LCT 535) as to what course to steer or what object on the beach to head for, and by constantly urging him to make his maximum speed, it was possible to hit the proper beach at nearly H-Hour. The leading LCT with DD tanks (LCT 535) beached at about 0632 hours . . . “[17]

The reports from Rockell’s OICs indicate they initially took fire in the vicinity of the Line of Departure, by which they actually meant the 6000 yard launch line. (The actual Line of Departure (LOD) was 3,500-4,000 yards out, but for some reason the DD/LCT crews all referred to the 6,000 yard line as the LOD). Fire became more intense and more accurate as they closed to the beach.

As with virtually all landings that day, the exact location they touched down can’t be precisely determined, although most leaders tended to believe they landed exactly on target, as Rockwell believed. A dissenting report came from Lt.(jg) J. L. Bruckner aboard PC567, which was the Primary Control Vessel for the Dog Green beach sector (Vierville-sur-Mere and the D-1 Exit), where four of Rockwell’s LCTs should have landed. That craft reported it was on station, 4,500 yards and at bearing of 210 degrees(T) from Dog Green at 0517 hours, well before Bucklew’s and Rockwell’s craft came along.[18] PC567’s report is a bit confusing. It first stated that it saw none of the four DD/LCTs slated for Dog Green and had no idea where they went. It went on to state that two ‘lost LCT(A)s’ reported in, and even though they were at the wrong beach sector, the PC waved them in. In fact, the two ‘LCT(A)s’ he mentioned (LCT-590 and LCT-591) were actually Rockwell’s two right-most DD/LCTs, the #7 and #8 in his formation.

Despite this error, PC567’s report contained two points of value. First, Rockwell’s right flank was off course so far to the east that two of the four LCTs (the #5 and #6 LCTs in the formation) missed reporting to the Primary Control Vessel and presumably landed in the next beach sector to the east (Dog White). CAPT Bailey, Commander, Assault Group O-2, observed in his own action report that PC567 “did not maintain station as accurately as it should.”[19] Since the current at that time was pulling PC567 to the east, that would mean Bucklew and Rockwell were even farther off course than suspected. And second, by the time they passed the Line of Departure, they were five minutes late. While this may have been at least partially overcome by Bucklew hectoring Rockwell to make best speed, Bucklew nevertheless reported they touched down two minutes late. It is not a terribly significant delay given the chaos of the landings. But it does tend to emphasize the meaninglessness of Rockwell’s oft-peddled claim that his was the first craft to beach on Omaha, touching down at 0629:30 hours.

Figure 4. The Landing. This image illustrates the beaching positions of Rockwell’s eight LCTs. The dashed LCT icons show the beach sectors they were intended to land on. The solid LCT icons represent the approximate sectors where they did beach - based on my interpretation of conflicting sources.

A Cruel Coast

The traditional account of the landing of the 743rd Tank Battalion has it that all 32 of the DD tanks of Companies B and C were delivered safely to the beach. That isn’t quite true. In drawing a contrast with the fate of the 741st Tank Battalion’s DD tanks, a bit of exaggeration crept into the story.

For one thing, ‘landing directly on the beach’ was a bit of a misnomer. With the draft of an LCT and the very gradual gradient on Omaha’s beach, the tanks would not land with ‘dry feet.’ They would be dropped into the surf, often with the water so deep it could drown out the tank engines. That is why the non-DD tanks, often called the ‘waders,’ were equipped with deep wading kits that protected the engines and had chimney-like ‘stacks’ that took the air intakes and exhaust vents above even the turret level. As a result, the DD tanks would need to keep their flotation screens inflated during beaching or risk drowning-out in the surf. However, this point was not appreciated by some the DD tank crews because the beach gradient at their training site in Torcross didn’t pose this problem. When the tanks beached there in training, they exited in shallow water. Misled by their training, almost all of the tankers deflated their skirts when they learned they would be put down ‘on the beach’, and the tankers aboard a couple LCTs even ditched ‘unneeded’ parts of their flotation equipment. As it would turn out, almost all of the tanks would exit in water requiring inflated skirts, and some would have to actually swim some distances—usually short—before touching sand. These errors would cost them precious time under fire while beached, and ultimately lives and tanks. It isn’t clear whether Rockwell and his OICs were aware of the different beach gradient at Omaha, or understood its implications. If so, it doesn’t seem to have been passed on to the tankers.

Company B’s Landing

The 16 DD tanks of Co. B were embarked on the last four LCTs in the column formation, which placed them on the right flank when the formation turned right into line abreast. The 743rd Tank Battalion S-3 (Operations) Journal includes an account of Co. B’s landing, stating they landed on Dog Green, which was their intended sector.[20] But given that only the farthest two LCTs on the right (#7 and #8 in line) encountered the Primary Control Vessel for that beach, and given this LCC was probably drifting too far east, it seems likely the lead two LCTs (#5 and #6) of that section landed on the neighboring Dog White.

The OICs of these four LCTs described their landings as follows (from right to left, facing the beach).

Ensign Robert B. Gilfert (OIC of LCT-590, #8 in line) reported:

“0630 Hit beach with rockets still falling around us.

“0630-0634 On beach waiting for tanks to go off. Were shelled by shore batteries and machine gun fire. Return fire with our 20mm gun and machine gun of first tank.

“0634 Last tank went off and we retracted from beach.”

Ensign George W. Novotny (OIC of LCT-591, #7 in line), provided the most bare-bones account, consisting of just these three paragraphs.:

“1. 0505 Received word to take tanks to beach. Tank men threw all launching gear overboard immediately.

“2. Hit beach Dog Green at 0630 and unloaded tanks. First tank was hit by 88 when five yards from LCT. Other tanks stopped alongside first tank.

“3. In my opinion launching gear should not be scuttled until last minute. If LCT should sink, tanks might float free or waves might permit launching at 1000 yards.”

Ensign Floyd S. White (OIC of LCT-713, #6 in column) ran into problems when beaching at H-5 minutes (0625 hours) about 50-75 yards shy of the Element C obstacles. When lowering the ramp, the ramp extensions were hanging askew, and the ramp was raised to discover the extension supports had been sheared off. The ramp was lowered again, but the lead tank commander hesitated; believing they would be dropped off in shallow water, his tanks had previously deflated their skirts. It took “about 15 minutes” to reinflate, but the supporting struts for the first tank’s canvas were not locked into place when the tank cleared the ramp. It sank straight to the bottom, the skirt not being strong enough to hold against the water pressure. After rescuing the tank’s crew, White retracted his LCT and beached again about 150 yards to the east, where “after a short delay, the other three tanks were successfully launched.” During this time, the ship was hit and set afire.” The choice of the word “launched” indicates they had to swim some short distance—presumably not very far. All these maneuvers resulted in the LCT not retracting the final time until 0710 hours, 45 minutes after its initial beaching.

Ensign William C. Cook (OIC of LCT-588, #5 in line) reported:

“At 0635 we beached as far as the ship could go on the beach. The captain thought the water might be too deep and would aid [?] them to inflate again. After doing this, they were able to reach the shore without any difficulty and the last I saw of them they were proceeding up the beach firing.”

From this it isn’t clear if any of these DD tanks had to swim.

The report of the first three LCTs reflect more intense enemy fire, as would be expected from the craft landing closest to the defenses of the D-1 draw. In addition to LCT-713 being set after, Gilfert on LCT-590 (the LCT closest to the D-1 Draw) lost three killed and two wounded during this beaching.

The account of Co. B’s landing contained in the S-Journal is brief and grim.