Omaha Bombardment. Part I: Setting the Stage

Perhaps the single greatest failure at Omaha Beach was the bombardment plan. Despite the efforts of 13 bombardment ships and dozens of supplemental bombardment craft, German defenses emerged sufficiently undamaged to virtually stop the invasion at the shoreline for the first hours. Many reasons have been advanced for this failure, to included a shortage of bombardment ships, too short of a bombardment window and the failure of the heavy bombers to hit the beach defenses.

This three-part series examines the facts behind the bombardment controversy and attempts to separate the valid criticisms from the popular misconceptions. This installment, Part I, explores the operational environment and how it shaped the basic concept of the landings, as well as how that constrained bombardment operations. Part II will examine in detail the bombardment plan developed for Omaha Beach, and Part III will analyze how effectively that plan was executed.

Join me to see what really lies behind the popular versions of the Omaha bombardment failure.

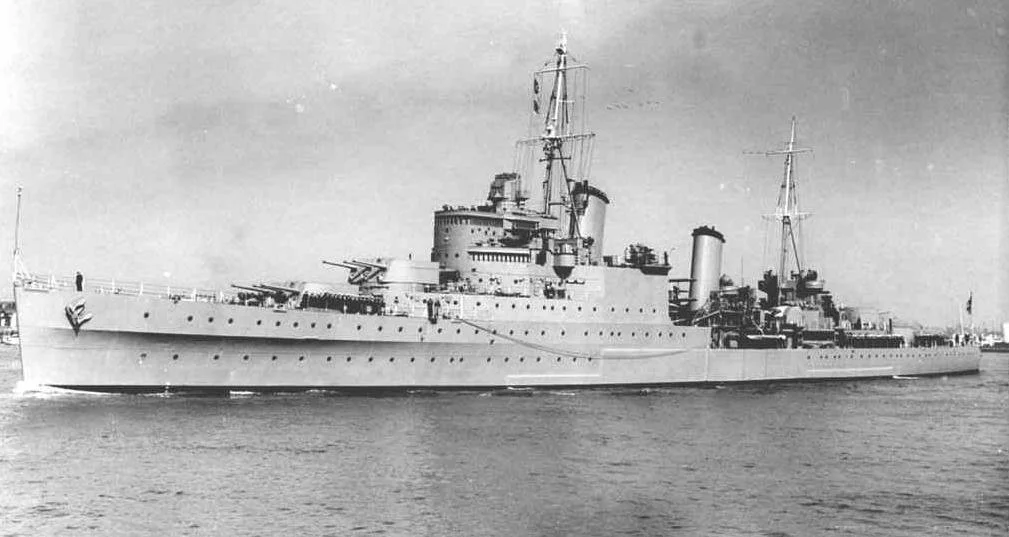

American Battleship USS Texas (BB-35) off Norfolk, Virginia in March 1944. The Texas was one of two WWI-era battleships assigned to Assault Force O at Omaha. She mounted ten 14-inch guns in five double turrets, and six 5-inch guns in casemate mounts. (NARA 80-G-63542)

The Failed Bombardment

One of the most infamous failures during the Omaha landings was the bombardment plan, a failure that saw infantry land in the teeth of strong defenses which had not been neutralized. There has been no shortage of critics or shortage of criticisms of this plan. There were not enough bombardment ships. There was too little time for bombardment. The bombardment relied too heavily on air power. The bombardment counted too heavily on makeshift fire support assets. And the list goes on.

And honestly, there is more than a grain of truth to each of those accusations. But what these critics—who, for the most part argued from their own single, narrow perspective—failed to consider were the constraints under which Neptune operated. Were there too few bombardment ships? Perhaps, but Eisenhower used all that he could wrangle from the Combined Chiefs of Staff. Was the bombardment window too short? Perhaps, but it was all the time that could be spared. Was there too much reliance on airstrikes and on ‘gimmick’ fire support craft? Perhaps, but these were necessary stopgaps to compensate for the paucity of bombardment ships. The fact is that the Neptune planners did not accept those limitations because they mistakenly thought they were the best solutions. No, they were accepted as the best options available in the face of limited resources, and within a unique and disadvantageous operational environment.

The stark fact is that the final bombardment concept was the product of numerous constraints and unavoidable tradeoffs with which the Neptune planners had to contend. Many painful compromises had to be made between equally important, yet conflicting considerations. As this series will illustrate, the bombardment would fall short at Omaha on 6 June due to several underappreciated factors which combined to produce a flawed plan and prevented effective execution of that plan.

HMS Glasgow (C21), a British Town class light cruiser assigned to Assault Force O at Omaha. She mounted twelve 6-inch guns in four triple mounts.

The Concept of the Assault

As the SHEAF command structure coalesced in the last months of 1943 and the beginning of 1944, the various new commanders began to reassess the plans left to them by LTG Frederick Morgan, who, as the Chief of Staff, Supreme Allied Commander (COSSAC) had conducted the invasion planning before General Dwight Eisenhower had been selected as the Supreme Allied Commander. Both General Eisenhower and General Bernard Montgomery (the 21st Army Group Commander-designate) had opportunities to briefly review these plans while still assigned to the Mediterranean theater, and had independently come to the conclusion that the invasion needed to be stronger and launched across a broader front.[1] After taking command of 21st Army Group (initially the land component of SHEAF) Montgomery formally proposed an expansion of the invasion in January, resulting adoption of the five-division plan and extension of the invasion front to include a landing on the Cotentin Peninsula (at Utah Beach, on the west side of the Vire estuary).[2]

Meanwhile doubts had been growing about the fundamental nature of the assault. The operational environment of the Mediterranean had influenced the evolution of amphibious doctrine over the course of several landings in that theater, resulting in a technique that Admiral Bertram Ramsay (the Allied Naval Commander-in-Chief for Operation Neptune) would term the Silent Assault. To oversimplify, this technique called for the invasion fleet to silently approach the objective area and land infantry assault waves well before dawn with little or no preparatory bombardment. By dawn, the initial infantry waves would secure a limited beachhead against light opposition, and larger craft carrying heavier weapons would land behind them as quickly as possible. It was a system that functioned well in areas of minimal defenses, manned by enemies not inclined to fight to the death, and in areas either isolated from reinforcements or that were difficult to reinforce. The technique stood at virtually the polar opposite extreme of the technique generally used in the Central Pacific campaigns. The objectives in the Central Pacific[3] were normally completely isolated, heavily defended and fanatically manned, which combined to demand extremely heavy preparatory fires, often lasting days.

GEN Morgan’s Outline Overlord Plan did not address whether the landings should be in daylight or at night,[4] but most of the key Neptune leaders had previously participated in landings in North Africa or the Mediterranean, and so brought with them to Neptune the expectation that a similar silent assault technique would be employed in Normandy.

But the Normandy coast was neither North Africa nor the Mediterranean. In some key respects, it was the worst case operational environment. The beaches were much more heavily fortified and heavily manned. That fact would normally call for serious preparatory fires before landing troops, which in turn would argue for a daylight attack. But this consideration collided with another operational characteristic.[5]

The extensively developed European road, rail and water networks enabled the enemy’s local reserves to be quickly committed, and similarly facilitated rapid deployment of his operational and strategic reserves from greater distances. Thus, every minute of delay between discovery of the invasion fleet and the first troops hitting the beach gave the enemy time to reinforce. As Samuel Elliott Morrison acknowledged in his History of United States Naval Operation in World War Two,

“They had to have tactical surprise, which a long pre-landing bombing or bombardment would have lost . . . Even a complete pulverizing of the Atlantic Wall at Omaha would have availed us nothing, if the German command had been given 24 hours' notice to move up reserves for counterattack."[6]

This consideration called for the absolutely shortest time possible between discovery of the fleet offshore and the first troops setting foot on the beach.

The Montcalm, one of two French La Galissonnière class light cruisers assigned to Assault Force O at Omaha. She mounted nine 6-inch guns in three triple turrets. (NARA 19-N-48998)

Perhaps the first to realize the significance of the different conditions was Ramsay. At least he gave the impression he was. In his diary he recorded that on 10 February 1944, he met with Montgomery to discuss the nature of the proposed landing operations.[7] He said he convinced Montgomery the silent assault technique was wrong for Neptune, although he did not specify exactly what he proposed in its stead. Although Montgomery had only recently arrived to assume his role, he had already pushed through his demand to expand the size of the invasion, underscoring his familiarity with the planning. And in that process, was undoubtedly influenced by one of his subordinate commanders.

Two months earlier, on 14 December 1943, Lieutenant General John T. Crocker (Commanding General, British I Corps) had conducted an analysis of the situation which had come to much the same conclusion as Ramsay’s. Quoting from Harrison’s Cross Channel Attack:

“The first essential, he [Crocker] said, was the development of ‘overwhelming fire support from all sources, air, naval and support craft ... to cover the final stages of the approach and to enable us to close the beaches. This requires daylight.’ Mediterranean experience, in his view, had shown that the effectiveness of naval fire depended on observation and that it had been much greater than was previously supposed. At least forty-five minutes of daylight, he estimated, would be necessary for full use of fire support, and he concluded that H Hour should be within one hour of first light.”[8]

That thinking was generally accepted and was incorporated into the Neptune Initial Joint Plan (issued 9 days before Ramsay’s diary entry):

“H Hour

“It is defined as the time at which the first wave of landing craft should hit the beach; which will be

“a. About l 1/2 hours after nautical twilight, and

“b. About 3 hours before high water.”[9]

This shows that at an early point the matter had been closely studied, that there was a recognition that the Mediterranean style assault was not applicable, and that a daylight assault shortly after dawn was called for. Over the following months, many debates would rage over the exact details, and the specific timing of H-Hour would be batted back and forth almost endlessly. One result was a later change to the above Initial Joint Plan paragraphs which added: “so as to allow a minimum period of thirty minutes daylight for observed bombardment before H Hour.” Nevertheless, the basic nature of the assault had been decided by 1 February. And both the senior naval commander (Ramsay) and senior ground commander (Montgomery) were in accord. As Ramsay stated in his report on Operation Neptune:

“7. The one fundamental question on which there had to be early agreements was whether to assault during darkness so as to obtain the greatest measure of surprise on the beaches, or whether to assault after daylight and to rely on the greatly increased accuracy of air and naval bombardment under these conditions. The decision which was made, to make a daylight landing, was in accord with experience in the PACIFIC against strong defenses, when the assaulting force possessed decisive naval and air superiority, and I am convinced this is the correct answer under these conditions.”[10]

So, daylight was essential to bring accurate preparatory fires to bear, yet the time to employ that fire support had to be severely curtailed in order to minimize the enemy’s opportunity to reinforce. Striking a blance between the two imperatives would not be easy.

Nevertheless, the azimuth had been set by the leaders, and the planners set about their tasks. Yet even as the Neptune planners came to grips with devising a new assault technique suited to the Normandy conditions, they had to contend with the longstanding shortage of naval assets. There had been few enough ships and craft to support the original three-division assault. Now, the expansion of the invasion to a five-division assault merely made matters much, much worse. The original intent was that the invasion would be primarily supported by British naval forces, but this expansion demanded greater commitments from the US Navy. And the US Navy was not receptive to any diversion of ships that would distract from its Pacific Campaign (not to mention its many other critical missions). We’ve previously discussed the resulting shortage in shipping and landing craft, so it is no surprise that bombardment ships were in short supply as well.

As Ramsay and Montgomery were grappling with these issues a new factor had come into play. German General Erwin Rommel assumed command of Army Group B on 15 January 1944 and immediately began to strengthen the defenses. The first indications of his impact were just being noticed by Allied intelligence in January and February, and their full implications would not be appreciated for several weeks. The scope and speed of Rommel’s activity would be an unwelcome surprise. The Neptune planners were struggling to cope with the challenges of the enemy defenses as they understood them in January and Februrary1944, even as the enemy was rapidly increasing the physical defenses and reinforcing those defenses with additional units. Rommel was moving the goalposts on the invaders, and the fact is that the Neptune commanders and their staffs would be involved in a game of catch-up for the next few months. A belated response to the multiplying obstacle fields saw the creation of the obstacle clearance plan and formation of units to execute it. And that plan would have to be executed in the initial act of the invasion as well.

American destroyer USS Satterlee (DD-625). The Satterlee was one of nine Gleaves class fleet destroyers assigned to Assault Force O at Omaha. The Gleaves class destroyers mounted either four or five 5-inch guns in single mounts. The Satterlee is picture here in Belfast Lough three weeks before D-Day. In the background are two more Gleaves class destroyers; all three ships were part of Destroyer Squadron 18 (DESRON18). (NARA 80-G-367828)

The First 120 Minutes

A full discussion of the many factors that influenced the selection of H-Hour at Omaha is beyond the scope of this installment, but I will touch on some of the more important aspects as they related to the bombardment plan. Essentially, the Omaha Assault Force planners (Admiral Hall’s CTF 124, working in conjunction with the Army V Corps) had to carefully orchestrate a complex sequence of actions within a roughly two hour period. Two factors would help define the beginning of the assault window. The first was light; specifically, the earliest time naval bombardment ships would have enough light to conduct observed fire. Sunrise on 6 June would be at 0558 hours, and they might be able to take advantage of the last few minutes of morning civil twilight as well, especially if spotting aircraft were available. The second factor was the tide; the Navy needed a rising tide to enable them to retract after unloading their landing craft, and low tide would be at 0530 hours. The end of the critical window would also be dictated by the tide, and that would be when it was so far up the beach that the obstacle clearance teams would have to cease work. That would be approximately 0800 hours. Ideally, the obstacle clearance teams needed to land as early as possible to have the most time to do their job, but the first wave of infantry had to go in before the obstacle teams, and the earlier they went in, the more open sand they would have to cross under fire. Potentially this could be as much as 350 yards, which would be suicidal. So, the first wave could not go in too early. As a result of all these factors (and many more) a critical window of roughly two hours was established for the start of the landings: 0558 hours (sunrise) to 0800 hours (the tide amid the obstacles). And in the middle of everything that had to take place in those two hours, the planners needed to squeeze in 45 minutes for air and naval bombardment, a figure that carried forward from Crocker’s analysis. As you can see, the final landing schedule entailed a series of cruel tradeoffs between equally vital but usually incompatible considerations.

To no one’s complete satisfaction, H-Hour was set at 0630 hours. However, it is important to keep this in context. Each and every H-Hour decision is a matter of compromising between the needs of different elements of the attack force. The more complex the operation is—and Neptune was about as complex as they come—the more tradeoffs are necessary. Having said that, it was clear it would be a rough two hours at Omaha.

The bottom line, as far as the bombardment mission was concerned came down, to 32 minutes between sunrise (0558 hours) and H-Hour (0630 hours). Hall’s planners moved the start of that window forward to 0550 hours, counting on the growing visibility at the end of civil twilight, and that was as close to Crocker’s 45 minutes as could be managed.

[As difficult as the conditions were for 6 June, it should be noted that H-Hour on the original invasion date, 5 June, was 20 minutes earlier, at 0610 hours. That would have meant most of the bombardment would have been conducted during insufficient light, likely resulting in less damage to the defenses and far higher casualties among the assault troops.]

The British escort destroyer HMS Tallybont, one of three Hunt Class (Type III) escort destroyers assigned to Assault Force O. These Hunt class escort destroyers mounted four 4-inch guns in two twin turrets.

Too Few Guns

Ideally, if you have less time to fire your preparatory bombardment (and Hall had not been happy with the 45 minutes he did have), you want to increase the number of guns firing in order to deliver the required metal on target. But, as noted above, Neptune as a whole was being conducted on something of a naval shoestring, and this held true for bombarding assets as well. Bombarding types of ships (destroyers, cruisers and battleships) were at a premium, especially with the US Navy, which was husbanding its fleets for Pacific campaigns. The British were no less reluctant to take capital ships from the Home Fleet, which was standing guard in case of a sortie by the remaining German capital ships.[11] To address this shortfall, in late December 1943, RADM Kirk (commanding the Western Naval Task Force - TF 122) sent Washington a list of requirements for bombardment ships; no action was taken. After the expansion of the assault to the five-division plan the following month, the deficit widened and pressure mounted for a greater US Navy contribution. The matter came to a head on 13 February at a dinner being held in conjunction with a conference to iron out landing craft allocations. RADM Cooke (chief planner for the US Navy’s Commander in Chief, ADM King) was present when Hall exploded in frustration over the lack of bombardment ships. Cooke reprimanded Hall for the outburst, but he also saw to it that three old US battleships and a squadron of nine US destroyers were provided.[12]

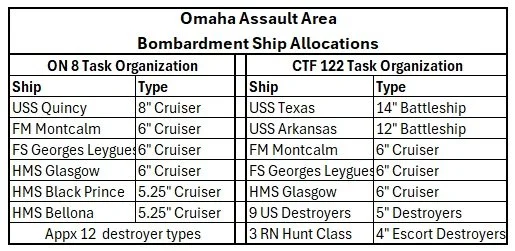

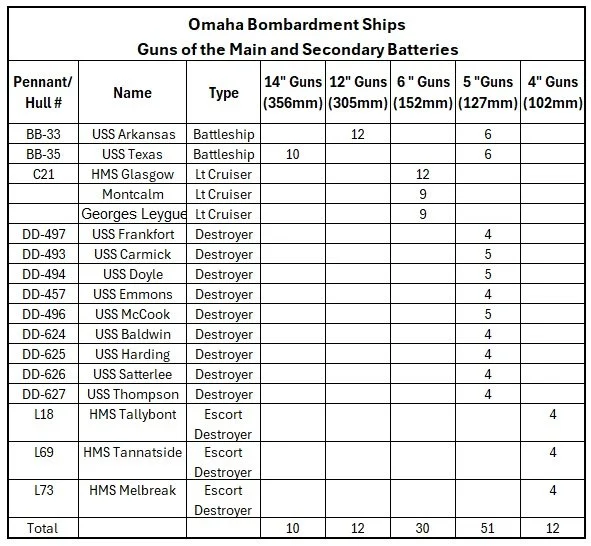

Initially, bombardment ships for Omaha, as allocated in Ramsay’s naval orders for Operation Neptune (ON 8, issued 14 April 1944, dealt with bombardment) amounted to: one heavy cruiser, five light cruisers and an unspecified portion of 22 destroyers and escort destroyers. (See Figure 1). It wasn’t much. By comparison, the US pre-war amphibious doctrine called for a bombardment force of three battleships, four light cruisers and 8-16 destroyers for an assault the size of the Omaha landings.[13] As measured by this doctrinal template, Omaha was under-supported when it came to naval bombardment.

A week later, RADM Kirk’s Western Naval Task Force (CTF 122) operation order was issued, and it reflected Cooke’s reinforcements, which were split between Omaha and Utah Assault Areas.[14] For Omaha, two battleships had been substituted for one heavy and two light cruisers (the third battleship Cooke had secured went to Utah Beach). The loss of three cruisers (nine 8-inch guns, sixteen 5.25-inch guns and eight 5-inch guns) for the gain of two old battleships (ten 14-inch guns, twelve 12-inch guns and twelve 5 inch guns) apparently suited Hall, an old battleship admiral. He gained heavier guns in his primary batteries and increased his secondary batteries by 50%. The punch these old WWI-era battleships offered was very welcome.

Figure 1. A comparison of the original bombardment ships allocated to the Omaha Assault Force under ON 8 and the final allocation as shown in the CTF 122 operation Plan.

What was perhaps less welcome in this new ship allocation was the assignment of the Royal Navy Hunt class escort destroyers. The US fleet destroyers were of the Gleaves class, which mounted either four or five 5-inch guns. The Hunt class escort destroyers mounted four 4-inch guns.[15] The 4-inch gun was not a bad weapon, and in fact, at 102mm was comparable in caliber to the 105mm howitzer that was the standard US divisional artillery weapon. But besides the smaller gun, the Hunts carried fewer rounds per gun than the Gleaves (250 vs 400).[16]

Figure 2 details the gunpower these ships mounted for naval bombardment.

Figure 2. A summary of the type and number of bombardment guns available on the battleships, cruisers and destroyers allocated to the Omaha Assault Force.

One hundred and fifteen guns sound like an impressive number, but was it an adequate number to get the job done? As we’ll see, that answer depended on how you define the job, and which part of the doctrinal template you chose to apply.

Two other points factor into that question, as well. First, not all of these guns would be available for softening up the beach. A significant percentage of them would be dedicated to counter-battery fire against enemy coastal artillery batteries, such as those on Pointe du Hoc and at Port en Bessin. Second, six of the 5” guns, mounted in the battleships‘ secondary batteries, would be on the unengaged sides of the ships, and not be able to bear on a target. So, the total of 5” guns, as shown in Figure 2, would be reduced by 12% to 44 guns.

Hall’s Force O (Omaha) was fortunate in one small respect. All of his US ships had arrived in the UK by 28 April, in sufficient time to prepare for D-Day, unlike at least one division destined for Utah that barely arrived in time. Information is scarce about participation of the US destroyers and battleships in Exercise Fabius I, the final D-Day exercise. It is known that USS Thompson did participate, and that tends to indicate the rest of Destroyer Squadron 18 (DESRON18), the formation these destroyers belonged to) did as well. After that exercise, DESRON18 held about a week of additional gunnery exercises. This training was no doubt valuable. Although all the DESRON18 destroyers had been in commission for over a year, they had primarily been tasked with convoy support missions. D-Day would be their first combat experience in shore bombardment. Although unbloodied and new to the shore bombardment role, there was no reason to doubt their ability.

The situation with the battleships is not entirely clear. In his Action Report on Operation Neptune, RADM Bryant (commanding Battleship Division 5, and within TF-124 framework he commanded CTF 124.9, which was the Bombardment Group) discussed bombardment training after arriving in the UK, but nothing in the area of the Fabius Exercise, likely due to the limited live fire ranges at the rehearsal area. The Texas had already seen combat during WWII, starting with Operation Torch. The Arkansas, which had spent the bulk of the war either as a training ship or on escort duty, had yet to fire a gun in anger in this war.

Supplementary Efforts

Clearly, more gunfire support was needed. To complement and reinforce the usual bombardment battleships, cruisers and destroyers, a number of other craft would provide supporting fires. Some of these were ad hoc solutions, some were systems new to the theater and not well understood, and some were such wild ideas that RADM Hall would dismiss them as gimmicks.

The first group in this category were the Duplex Drive (DD) tanks. Although part of the Gunfire Support Group (as distinct for the Bombardments Group consisting of the ‘real’ bombarding battleships, cruisers and destroyers), they would play no role in the preparatory bombardment; their role was to support the leading assault waves after landing. For that reason, and since I have discussed them thoroughly in an earlier blog series, I will skip over them here.

The second element consisted of thirty-two Sherman tanks (and 16 tank dozers) that would ride in on 16 LCTs to beach at H-hour. At the front of these LCTs (either LCT(A)s or LCT(HE)s) wooden platforms had been installed which raised the two front Shermans high enough to fire over the ramps. During the run into the beach, these tanks would provide “drenching fire” that hopefully would suppress the defenders as the first two waves landed (the first infantry wave and the gap clearance teams). As such, their role in the bombardment plan was marginal, and I’ll only lightly touch on them in the rest of this series.

The next group consisted of the Landing Craft, Tanks (Rocket) (LCT(R)s), which were LCTs fitted out with approximately a thousand 5-inch rockets. Following at a distance behind the first wave, these craft would loose their rockets so that they would impact when the first wave was 300 yards offshore. The desired impact area was supposed to be 200 yards deep and 400-700 yards wide (for an impressive theoretical density of one rocket for every 80 to 140 square yards). There were nine of these craft for Omaha.

There would also be five Landing Craft, Gun (Large) (LCG(L)), each equipped with two 4.7” guns (120mm). These craft were to operate close inshore and were assigned to engage specific targets on the beach during the last 10 minutes before H-Hour.

The next fire support category is perhaps a measure of how desperate they were to scrape up additional fire support. The 58th and 62nd Armored Artillery Battalions were equipped with M7 Priest self-propelled artillery vehicles, each mounting a 105mm howitzer. The 36 howitzers of these battalions would be mounted in 10 LCTs, and fire from those craft over the heads of the first waves. The LCTs were not stable gunnery platforms, and they would have to maintain about a 4-6 knot speed to minimize rolling and plunging. Gunnery under those conditions would be challenging to say the least, with changes in range requiring constantly updated firing data. Still . . . thirty-six 105mm howitzers were the theoretical equivalent firepower of nine additional Hunt class escort destroyers, and that was potentially a significant addition for a task force that considered itself starved for gunnery ships. At least it would be if there was some way to ensure their rounds landed somewhere close to the intended targets. In reality, they were expected to provide nothing more than what one would charitably describe as general area suppressive fire, if one wasn’t too particular about which area would actually be hit.

Also used were class 461 patrol craft (174 feet long, 280 tons and a crew of 65) which served as the primary control craft for various beach sectors. There were 6 of these, each mounting a single 3-inch gun, and each was assigned a specific target.[17]

One other category of craft would provide suppressive fire, though these were so small they were not even assigned targets in the bombardment plan. These were 21 Landing Craft, Support (Small), or (LCS(S)). Equipped with machine guns and 48 rockets, they would accompany the leading waves to beach and provide the last second suppressive fire for their accompanying landing craft.

It would appear everything that could be reasonably done to supplement the bombardment mission (and some that may not have been quite so reasonable) had been thrown into the mix. Hall, the old battleship sailor, quite naturally bemoaned having to employ such a ragtag force, but given his shortage of ‘real’ bombarding ships he had no choice.

B-24 heavy bombers, such as this one, were incorporated into the bombardment plan for Omaha Beach.

Air Bombardment

Various air operations were mounted in support of Operation Neptune involving all manner of aircraft. For the purpose of this discussion, we’ll focus on the heavy bombers, whose primary mission had been strategic bombing, but had been incorporated into the tactical bombardment of the assault areas on D-Day. These bombers had two roles. During the hours of darkness, early on D-Day, night bombers would attack the German coastal artillery batteries flanking the beach, in the vicinity of Pointe du Hoc to the west and Port en Bessin to the east. The second role, commencing shortly after sunrise, was to strike the beach defenses. Approximately 329 B-24 bombers of the Eighth Air Forces’ 2nd Bombardment Division would strike the beach defenses in the Omaha Assault Area at the same time as the naval bombardment. [18] As impressive as that number is, the amount of their bombs that could reasonably be expected to actually hit the beach defenses—even had the weather been perfect—was far less than is generally realized. In the next installment we’ll examine this point in more detail. For now, suffice it to say that even had the air bombardment gone as planned, its actual potential effect on the beach defenses has been greatly overstated.

The Purpose of Bombardment – Destruction or Neutralization?

Even as Ramsay, Hall and the other naval leaders were trying to obtain additional bombardment assets, they were embroiled in another debate involving the basic question of what exactly was the purpose of the bombardment. To be more precise, what effect was the bombardment expected to achieve? The general statement of ‘pave the way for the assaulting troops’ meant nothing in a tactical sense.

The two camps in this debate were those who believed the bombardment must achieve destruction of the enemy defenses (or at least a substantial portion of them), and those who felt that goal was not possible, and believed neutralization of the enemy defenses was all that was practical. To quote the US Navy’s Landing Operations Doctrine (F.T.P. 167):

Neutralization.--Neutralization fire is area fire delivered for the purpose of causing severe losses, hampering or interrupting movement or action and, in general, to destroy the combat efficiency of enemy personnel. In the usual case, neutralization is only temporary and the target becomes active soon after fire ceases. Neutralization is accomplished by short bursts of fire of great density to secure the advantage and effect of shock and surprise. Most targets engaged by naval gunfire will be of the type for which neutralization is appropriate.

Destruction--The term is applied to fire delivered for the express purpose of destruction and when it is reasonable to expect that relatively complete destruction can be attained. Destruction should be attempted only under favorable conditions of target designation and observation.[19]

A good example of the proponents for the destruction school of thought was MG Charles Corlett. Corlett had served in the Pacific, commanding first the Kiska Task Force, and then the 77th Division during the assault on Kwajalein. He was then brought to the European Theater and given command of the XIXth Corps, which was scheduled to land on Omaha Beach shortly after D-Day. After the mistakes at Tarawa, much greater emphasis was given to preparatory bombardment for the Kwajalein landings, and Corlett believed the lessons he’d learned in that operation were ignored in the run-up to the Normandy landings. But those lessons were largely not applicable. At Kwajalein, Corlett had been able to secure a number of small islets close to the main objective and landed forty-eight 105mm howitzers and twelve 155 howitzers—his entire division artillery—on one of them. All while four battleships, two cruisers and 4 destroyers bombarded Kwajalein throughout the day of D-1. Harassing fires were maintained through the night by both the Army and the Navy (battleships Idaho, New Mexico, cruiser San Francisco and their destroyer screen). A large scale bombardment incorporating all arms was conducted the next day in support of the main landings on Kwajalein itself.

There are few, if any, relevant lessons here for the Normandy landings. Corlett didn’t have to worry about the possibility of Japanese reinforcing divisions—to include perhaps a panzer division or two—rolling up while he took a day for preliminary operations. He didn’t have to worry about nearby E-Boat or U-Boat bases or Japanese air formations stationed within range. He was able to outflank the Japanese seaward defenses by landing from the less defended lagoon side. And Kwajalein was only 2.5 miles long and 800 yards wide, flat, lacking beach obstacles and mostly lacking vegetation. And it still took him longer to secure the island than it would take to secure the equivalent beach area at Omaha.

The comparison really falls apart when one considers the preparation. The Kwajalein naval bombardment totaled something less than 7,000 rounds during D-Day, most of which were fired during the beach preparatory bombardment. The Omaha Beach bombardment was scheduled to deliver 6,297 rounds for the preparatory bombardment alone. So, despite having more and heavier naval gunfire for Kwajalein, the planned Omaha bombardment was effectively equivalent, if not perhaps even greater. The real difference was not so much the naval bombardment, but the support provided from Corlett’s own Army guns. The 60 howitzers that were landed the previous day consisted of the entire 77th Division Artillery. And those 60 guns—whose accuracy had the advantage of solid ground, not rolling ships—fired 29,000 rounds during Kwajalein’s D-Day.[20] At Omaha there was no convenient island to preposition Army firepower, and even if there had been, there was no time to emplace it or fire a prolonged barrage. The Pacific model simply did not fit.

Corlett was an excellent general, and did a fine job commanding the XIXth Corps, so much so that he was later transferred back to the Pacific to command another corps for the planned invasion of Japan. But in pressing for a Pacific-style bombardment, he’d brought the wrong experience to the Normandy operational environment. He was bitter at the way he perceived his advice was ignored within SHAEF, but his advice was wrong.

Despite the inapplicability of the Kwajalein model, RADM Hall nevertheless embraced it to support his position:

“Using Kwajelein [sic] as a basis for a rough comparison, and disregarding other considerations, the landing of four times the number of troops against three time the defensive strength would call for an amount of naval gunfire support at Omaha many time greater than that employed at Kwajelein. Yet the weight of metal delivered at Omaha defenses was one-third that used at Kwajelein . . . Though the amount of naval gunfire to be delivered in a given situation cannot be arrived at mathematically, and though naval gunfire alone will not necessarily insure a successful landing . . . the foregoing rough comparative figures will serve to substantiate the conclusion that Omaha Beaches during the pre-landing phase, not enough naval gunfire was provided.”[21]

Probably the best proponent of the neutralization school of thought was Ramsay himself. He was influenced in this matter by a report titled "Fire Support of Sea-Borne Landings Against a Heavily Defended Coast” (the so-called Graham Report).[22] Although Graham was a Royal Air Force officer and his report focused primarily on the air contribution, it provided two insights that would largely govern the naval bombardment plan as well.

“a. Casemated batteries probably could not be destroyed by bombardment, but could be sufficiently neutralized to render them acceptably ineffective until the army could capture them. The report also calculated in detail the weight of fire required to do this.

“b. Beach defenses could best be neutralized by "beach drenching," which would force the defender underground and numb his mind and nerves. Aimed fire in the dust and smoke of battle would be less likely to accomplish this.” [23]

In other words, direct hits on individual bunkers, weapons positions and concrete troop shelters were highly unlikely with any reasonably sized naval bombarding force, so the emphasis should be on the more achievable goal of neutralization. (Graham’s final sentence in that quote would prove prophetic.)

This thinking was translated into Ramsay’s ANCEX orders.

“2. The object of the naval bombardment is to assist in ensuring the safe and timely arrival of our forces by the engagement of hostile coast defenses, and to support the assault and subsequent operations ashore.

“This will involve the following tasks:

“(a) Neutralization of coast defence and inland batteries capable of bringing fire to bear on the assault beaches or sea approaches until each battery is captured or destroyed,

“(b) Neutralization or destruction of beach defenses during the final approach and assault.”[24]

While the wording of this order included the term ‘destruction’, any such results would be incidental, and they were not to be counted on.

This focus was rooted in a firm grasp of reality. Not only was there not time available for a more comprehensive bombardment, but a significant portion of the available firepower could not be dedicated to shelling the beach defenses. As paragraph (a) of the above quote specified, the bombarding ships also had the defensive mission to neutralize any coastal artillery positions that might threaten the landing. And that requirement would demand a large portion of the cruisers’ and battleships’ firepower. At Omaha, for instance, the Texas fired not a single 14-inch projectile on the principal beach landing sectors during the preparatory bombardment; every single one of the 262 14-inch rounds allotted for its preparatory bombardment was targeted on or near the coastal artillery battery at Pointe du Hoc. Similarly, the entire firepower of one of the three cruisers was dedicated to neutralizing German guns in the vicinity of Port en Bessins.[25]

In fact, battleships were allocated specifically on the basis of the number of key coastal artillery batteries that threatened an assault area, and Omaha had just two: Pointe du Hoc, and Longues-sur-Mer - and the latter was within the Gold Assault Area and was to be targeted by a capital ship belonging to the Gold Assault Force. So, this interpretation of the doctrinal template did not indicate Omaha was under-supported in battleships or cruisers

Ramsay’s objective of neutralization focused on what he thought was possible, and in this he was supported by the very same FTP-167 that Hall had selectively cited. That publication specified that a four- or five-gunned 5-inch destroyer could neutralize a 200 yard by 200 yard area with 80 rounds of rapid fire. Further, it could neutralize six such targets an hour. As the bombardment period was scheduled for 40 minutes, each destroyer should have been able to neutralize four targets. But no destroyer at Omaha was assigned four targets. One destroyer was assigned to just a single target, most were assigned just two targets, and only one was assigned three targets. The destroyers should have had ample time and ammunition to neutralize their assigned targets. A similar analysis for the cruisers produces the same results. Glasgow, for instance, was assigned two targets within 200 yards of each other (its area of coverage for a twelve-gun broadside was 300 yards by 300 yards), and the ship was allotted more than three times the doctrinal number of rounds necessary to neutralize those targets. So, a persuasive argument can be made that there was not in fact a shortage of bombardment ships at Omaha. The fact that none of these targets was actually neutralized by the D-Day preparatory bombardment suggests we need to examine whether there were shortfalls in how the bombardment was executed, as opposed to faulting the number of ships available.

In the next installment, I will examine the actual bombardment plan, illustrate how it was organized and show how the targets selected for the various supporting ships would combine to (hopefully) create a fully integrated neutralization of the defenses at key locations across the length of Omaha Beach. In the third installment I will examine how well that plan was executed, and how it fell short.

Concluding Thoughts

One of the continuing themes of this Omaha Beach Series has been that Neptune was under-resourced, and that chronic lack of resources affected how the operation was executed and how well it succeeded. In the matter of the bombardment mission, this theme is not as applicable as I initially thought. Yes, one reading of the amphibious doctrinal template definitely called for more bombardment ships and greater time for the bombardment. But the one true limiting criterion was the time allocated for the bombardment, and that was dictated by hard realities. The debate of neutralization vs destruction was fruitless, as destruction simply could not be achieved within a timeframe suited to the operational environment.

Further, even if RADM Hall had been allotted more bombardment ships, there is a real question as to whether he could have employed them profitably in the crowded fire support areas. As we’ll see in a later installment, some of the ships he did have were not used to their full extent due to other bombardment ships masking their gun-target lines.

Any commander with any common sense instinctively wants more combat power, especially fire support, but few ever get what they want. Or even need. The mark of a good commander is how well he employs the fire support he does have. And that’s the question we will pursue in the following installments: was the bombardment plan for Omaha as efficient as it reasonably could have been, and did its execution on 6 June live up to its objectives.

Finally, I want to stress once again that simplistic analyses continue to grossly misrepresent how the plan developed. An example is this quote from a 1998 US Naval Institute article:

“It is more accurate to state that the Allied leaders and planners of the Normandy invasion did not display the level of professionalism expected this late in the war. For the Normandy invasion, the Allied commanders ignored tested doctrine and thus ignored the cumulative body of knowledge in amphibious operations gained through hard-fought battles in North Africa, Sicily, and Tarawa. Montgomery and Bradley used an unproved means to deliver the vast majority of the combat power needed to overcome the defense. They failed to trouble-shoot their primary plan—air power—and to fully a back-up plan [sic]—naval gunfire, and so, the Allied plan failed at the most heavily defended beach.“[26]

That passage is particularly objectionable as it placed the entire blame for the naval bombardment on two Army officers, completely ignoring the fact that naval bombardment was, obviously, a naval responsibility, and the bombardment plan was written by naval staffs and approved by naval commanders. Indeed, the landings were commanded by naval officers, with Army commanders in subordinate positions. Given this, it’s hard to believe the author chose to completely ignore the role of Ramsay in the Neptune planning, or the US Navy’s role in allocating bombardment ships. This is not to deny army involvement, for of course it was a joint operation, and ground commanders presented considerations that had to be factored into the many painful trade-off decisions. But to place all the blame on Montgomery and Bradley is patently absurd.

So too was that the comment that Bradley and Montgomery “ignored the cumulative body of knowledge” gained in the course of Mediterranean operations. They didn’t use many of the Mediterranean (or Pacific) techniques simply because: 1) they didn’t have the naval combat power necessary; or 2) the operational characteristics of the Normandy coast made those techniques either irrelevant or extremely dangerous to the chances of success.

The author is marginally more on point when he says they failed to trouble-shoot their primary plan and have some sort of backup plan in case the air support failed. Ideally, that’s a very good point, and all good plans should have such contingencies. But it is one thing to hurl that doctrinal accusation, and quite another to imagine what possible contingency plan was feasible. Could they magically draw on three or four more battleships when, at H-15, the bombers hadn’t arrived? Did they have the option to delay the Omaha landings – and only the Omaha landings - until better weather showed up? No. Of course not. Such criticism is meaningless if there is no better alternative.

The weather for Neptune was a gamble. A famous one. A dangerous one. And while it had tragic consequences for the landings at Omaha Beach and the airdrops of the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions, it also ensured priceless surprise across all the assault areas, from the tactical level through the strategic level. The weather that foiled the air support at Omaha also permitted the vast invasion fleet, sailing from dozens of ports, to miraculously arrive off the beaches undetected. And that surprise worked in the favor of the Omaha landings.

Rare is the commander who has the luxury of ample assets for an operation. At Omaha, no more ships were to be had. No more time was available. And the weather was beyond anyone’s control. ADM Hall had what he had to work with. It’s as simple as that. The question before us in the next installment is, how well did Hall use the assets he was provided?

[1] Pogue, Forest, United States Army in World War II, The European Theater of Operations: The Supreme Command (CMH Publication 5-6), Center of Military History, United States Army, Washington, D.C., 1989, pg. 108.

[2] An additional invasion area was also added in the Eastern Naval Task Force sector.

[3] As opposed to GEN MacArthur’s Southwest Pacific theater, where the geography generally enabled the selection of generally lightly held or undefended beaches.

[4] Harrison, Gordon, Cross Channel Attack, Center of Military History, U.S. Army, Washington, D.C. 1993, pg. 73.

[5] This is not to overlook several important advantages the theater offered, such as being within fighter range of the UK, the relatively short distances between staging bases in the UK and the invasion beach, and many others.

[6] Samuel Eliot Morison, History of United States Naval Operation in World War Two, Vol XI, The Invasion of France and Germany 1944-1945, Little, Brown, and Co., Boston, 1957. P. 152-3.

[7] Love, Robert and Major, John, editors, The Year of D-Day; The 1944 Diary of Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay, The University of Hull Press, 1994, pg. 24.

[8] Harrison, pg. 189.

[9] Neptune, Initial Joint Plan, (NJC 1004), dtd 1 Feb 1944, see Section V, Assault Phase.

[10] Ramsay, Bertram, Report by the Allied Naval Commander-in-Chief Expeditionary Force on Operation Neptune, pg. 6 (covering letter).

[11] Morison, pp 55-56.

[12] Godson, Susan, Viking of Assault; Admiral John Lesslie Hall, Jr., and Amphibious Warfare,1982, University Press of America, pg. 124.

[13] Department of the Navy, F.T.P. 167, Landing Operations Doctrine, 1938, US Government Printing Office, pg. 122.

[14] CTF-122 Operation Plan No. 2-44, dtd 21 April 1944, Task Organization.

[15] As the primary mission of these escort destroyers was to protect convoys from submarines, their main battery did not require larger guns. In a similar vein, many of the US destroyer escorts were armed with 3-inch guns.

[16] CTF-122 Operation Plan No. 2-44, dtd 21 April 1944, Appendix 1 to Annex D. See also ANCX Naval Operation Orders for Operation Neptune, ON 8, Appendix III.

[17] The 3-inch gun is small by naval standards, but with a bore of 76mm, it compared favorably with the 75mm guns mounted on the Sherman tanks. The 3-inch guns that made up the tertiary batteries of the battleships also would provide good service on D-Day. Although not incorporated into the bombardment plan.

[18] Hennessy, Juliette, US Air Force Historical Study No. 70; Tactical Operations of the Eighth Air Force, 6 June 1944 – 8 May 1945, USAF Historical Division, Air University, 1952, pg. 25. There are conflicting reports on this number, and the matter will be examined further in the next installment.

[19] Landing Operations Doctrine, United States Navy F.T.P. 167, 1938, Ch V.

[20] Crowl, P and Love, E, United States Army in World War II, The War in the Pacific: Seizure of the Gilberts and Marshalls (CMH Publication 5-6), Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army, Washington, D.C., 1955. Chapter XIV, pg. 231.

[21] COMINCH P-006, Amphibious Operations, Invasion of Northern France, Western Task Force, June 1944, pg. 2-27

[22] See Ramsay’s Report by the Allied Naval Commander in Chief, Expeditionary Force on Operation ‘Neptune’, dtd October 1944. Vol I, Annex 5, pg. 64

[23] United States Naval Administration in World War II. United States Naval Forces, Europe. Volume V, Operation NEPTUNE - The Invasion of Normandy, 1948, pg. 489

[24] Allied Naval Commander in Chief, “Expeditionary Force, Operation Neptune, Naval Operations Orders,” dtd 10 April 1944, pg. 124.

[25] And that was just what the plan anticipated. In the event even more firepower was required for Port en Bessin.

[26] Lewis, Adrian, The Navy Falls Short at Normandy, US Naval Institute History, Dec 1998, Vol 12, Number 6.

The Duplex Drive Tanks of Omaha Beach, Part (f) Conclusions and Final Thoughts

This is the concluding installment in my six part dep dive into the facts surrounding the employment of Duplex Drive tanks at Omaha Beach. In this analysis I recap the roles played by the prominent figures in the saga and the degree to which they contributed to the outcomes on D-Day. Also is included a brief review of how the commanders at Utah, Sword, Gold and Juno Assault Areas planned for employment of their DD tanks, and how the results at those beaches compared to Omaha.

The saga of the Omaha Duplex Drive tanks is in many ways symbolic of Operation Neptune itself. The need for these tanks was a direct result of the alliance’s strategic dilemma: despite nominally giving the invasion high priority, it was unable or unwilling to commit sufficient naval assets to the task. One of the results of this mismatch between strategic lines of effort and force priorities was the critical shortage of bombardment ships for Neptune. The eventual solution was to seize on an experimental concept, throw it in on the first wave of the assault, and hope for the best.

On the one hand we see in this the genius of innovation, flexibility and industrial brute force, all key components of the eventual Allied victory. The fact that the industrial base could convert 200 Sherman tanks into duplex drive variants and ship them to the United Kingdom in a matter of just a couple months was an astounding feat (not to overlook the conversions being produced in the UK). But that kind of improvisation often contains the seeds of failure, usually in the form of inadequate engineering or inadequate production quality. And so it was here. The design of the duplex drive kit was so immature that the first thing they had to do when they reached the United Kingdom was apply fixes to the struts to keep them from collapsing. Given the brutal nature of the English Channel, that ‘fix’ would fall short.

An Extract from Commander, 3rd Armored Group memo to MG Huebner, Commander, 1st Infantry Division, addressing DD tank training. This paragraph highlights the deficiencies of the newly arrived duplex drive Sherman conversions.

And that illustrates the leitmotif which wove through the Neptune planning. It was in many ways characterized by a large scale effort to improvise solutions to problems which sprung, as often as not, from poor strategic planning and the enemy’s refusal to passively await a beating. In virtually every category, the planners were scrambling to find the means to achieve the ends. Bombardment ships, landing ships, landing craft, escorts, minesweepers, transport aircraft for airdrops - all were critical shortages. Sometimes units or materiel were found to fill the gap, but these were usually ad hoc, untested or ill-trained. And too often the invasion had to make do despite the shortages.

It is important, however, to keep this in context. War-by-alliance is a difficult endeavor, especially one being fought across the entire globe in numerous theaters, each with its own unique demands, and all clamoring for a share of vast, yet limited resources. The point of the preceding paragraphs is to highlight the limitations which hampered the planning and execution of D-Day. It is not intended to lodge a blanket indictment of LTG Morgan’s COSSAC or GEN Eisenhower’s SHAEF. Nor is it intended to criticize the wisdom of the Combined Chiefs of Staff or the political leadership of the allied nations. Certainly, individual decisions by each and every one of those bodies can be questioned, and sometimes, as they say, ‘mistakes were made.’

But that isn’t the point. All war is characterized by friction, inadequate resources, tradeoffs and sub-optimal solutions (the least bad options). Operation Neptune was no different. And despite the challenges and near chaos, it did succeed. Not as cleanly or easily as planned (or hoped), but assaults on defended shores seldom are.

The question here, however, is how effective were the commanders, their staffs and the executing units in coping with the limitations to make it all work. In some cases it was a matter of doing a familiar mission, but with green, perhaps ill-trained, units. In other cases, it was making the best of the least bad alternative. Which brings us back to the DD tanks. A new ‘gimmick’, inadequately designed and tested, hurriedly produced, not well suited for the waters in which it was to operate - yet necessary, if not vital, for want of a better solution. They were indeed the least bad solution. But that didn’t make them the wrong solution.

So, it is now time to recap the preceding five installments with an eye on how well each echelon addressed, helped or hindered the effort to land 64 swimming Sherman tanks on Omaha Beach at 10 minutes before H-Hour.

What I hope I have provided in this series is the most comprehensive body of research on the DD tank effort to date, as well as a detailed analysis of that information. To repeat a caution from an earlier installment, the saga of the DD tanks is so thoroughly replete with conflicting reports and questionable firsthand accounts that any conclusion depends entirely on which imperfect source you reject, and which you decide to accept. Others will no doubt weigh the sources differently and come to different conclusions. What follows represents my evaluation after more than a year’s study of the topic.

Two of three DD tanks landed directly on Easy Red Beach Sector by Ensign Henry Sullivan’s LCT-600. Photo by Robert Capa.

The 6,000 Yard Line.

One of the more curious aspects of the DD tanks saga was the disregard paid to the advice of the two men who had become experts in their use. After conducting an intense six-week training course for DD tanks and LCTs, Lt.(jg) Dean Rockwell and MAJ William Duncan were as much of experts on the matter as anyone else in Western Naval Task Force. Duncan ran the school to train the DD tankers and Rockwell’s LCTs supported the training. At the end of that training program, both men submitted reports. Rockwell noted that DD tanks “can be launched 3-4,000 yards from shore and reach a specified beach.” [1] Duncan noted that the tanks had been launched from as far out as 6,000 yards, but also noted that in launches of more than 4,000 yards out, six cases of non-fatal carbon monoxide poisoning occurred.[2] He therefore recommended they “not be launched more than 4,000 yards from the beach.”

Having received recommendations from their own designated experts, the powers that be ignored that advice and decided the appropriate launching distance would be 50% to 100% farther than recommended. They would launch at 6,000 yards.

In deciding this, they not only disregarded the advice of their own ‘experts’, they acted counter to their own best judgements. After the failures of D-Day, key naval figures were quick to claim they had always thought the DD tanks were a hairbrained idea. RADM Hall is perhaps the most notable among this crowd. Yet despite those supposed misgivings, they directed the launching of the ‘unseaworthy’ DD tanks at distances far greater than recommended. Their supposedly strong misgivings were so far at variance with what they directed in their orders that one must doubt whether those misgivings were authentic, or were merely post-debacle attempts to distance themselves from the consequences of their own orders.

The unfortunate fact is that there is no indication as to who was the original father of this decision. The highest level order citing that distance was RADM Kirk’s order for the Western Naval Task Force, however similar guidance was in effect at every beach, whether American, British or Canadian (at the British and Canadian beaches, the launch line was even farther out – 7,000 yards).[3] This would seem to indicate the policy came from Admiral Ramsey or even General Montgomery. Yet there is no record of any such order coming from either man.

There may have been grounds for this 6,000 yard decision. The fear of enemy coastal artillery may have imposed this caution; after all, launching required the LCTs to remain almost stationary, making for an easier target at closer ranges.[4] This possibility is underscored by the fact that at the British and Canadian beaches, instructions were not only to launch the DD tanks at 7,000 yards, but be prepared to launch them from even farther out if under fire from shore batteries.

Nevertheless, the 6,000 yard line stands at the apex of the DD tank fault pyramid, not necessarily because of the degree of the ensuing damage it may have caused, but because it so perfectly illustrates the lack of common sense brought to bear on this matter.

A Cascading Series of Errors

At Omaha, the confusion started with RADM Hall and subsequently infected all lower echelons. It began with Hall’s initial decision for apportioning responsibility. COL Severne MacLaughlin (Commander, 3rd Armored Group, the parent headquarters for both the 741st and 743rd Tank Battalions) reported Hall’s initial plan was for MG Gerow to make the decision if the weather was bad.[5] (Gerow, the V Corps Commander, would be with Hall aboard his command ship the USS Ancon, 23,000 yards offshore in the Transport Area.) In other words, Hall tried to remove himself completely from the matter.

Recognizing this was entirely unsatisfactory, MG Bradley (commanding the First U.S. Army) sent his letter to RADM Kirk, insisting on two points: 1) that the decision be made by the Assault Force Commander, with advice from the Landing Force Commander; and 2) that the decision should not be delegated to individual craft level. Although RADM Kirk changed his order (CTF 122) to allow breaking radio silence prior to H-Hour to facilitate such a decision, Hall rejected the idea in his own order. As far as can be determined, no answer on the record was provided in response to Bradley’s letter, and there is scanty and conflicting documentation on Hall’s decision on the matter before 6 June 1944.

In the wake of the confusion of responsibility on D-Day, Hall belatedly penned an apologia in his 22 September endorsement of Rockwell’s report. In it he attempted to show that he had provided clear guidance on the launch-or-land decision.

“2. The question as to who should decide whether to launch DD tanks was discussed at length by the Assault Force Commander with the Commanding General, Fifth Corps, U.S. Army and the Commanding General, First Infantry Division, U.S. Army. For the following reasons it was agreed that the decision should be left to the Senior Army Officer and the Senior Naval Officer of each of the two LCT units carrying DD Tanks:

“(a) They had more experience than any other officers in the Assault Force in swimming off DD Tanks from LCTs.

“(b) The decision should be made by someone actually on the spot where the launching was to take place and embarked on an LCT rather than on a large vessel. A decision under such conditions should be sounder than one made on a large vessel miles away where the sea conditions might have been much different.

“(c) If a decision were to be made elsewhere and action had to await an order, confusion and delay might result in the absence of such an order, and it was anticipated that communications might be disrupted by the enemy action so that it would be impossible to transmits orders by radio.

“NOTE: The two unit commanders were to inform each other by radio of the decision reached.”[6]

It is impossible to miss the unintended irony in the concluding note, given the fear of enemy jamming in the preceding paragraph.

In military vernacular, ‘discussed at length’ is usually a euphemism for ‘there were strong and irreconcilable disagreements.’ Similarly, in that context, the phrase ‘it was agreed’ generally means the commander made a decision over objections of key subordinates, who ultimately had to go along with the boss’ decision. Despite the false patina of unanimity, that paragraph indicates opinions were sharply divided.

The reasons Hall laid out for his decision did have the virtue of having some merit and might have been convincing were it not for his original stance. In that original stance, he would have had Gerow making the decision under the identical ‘limiting’ circumstances (23,000 yards offshore aboard a large and stable ship), and Hall was just fine with that. But after Bradley’s letter of protest, the decision was kicked back to Hall, and suddenly the conditions that Hall thought were fine for Gerow’s decision-making, were now completely unacceptable if Hall himself had to make the decision. This cast the rationale listed in Hall’s apologia in their true light: they were not put forward as sound tactical considerations, they were merely convenient pretexts that would enable Hall to again avoid responsibility in the matter. In Hall’s revised analysis, such a decision could only be made by a man ‘on the spot’ in the boat lanes with expertise in the matter of DD tank launchings, which, not so coincidentally, ruled himself out.

From this, I believe Hall’s primary motivation clearly was to avoid any personal responsibility for the decision to launch the ‘gimmicks’ in which he had no faith. And this ‘hands off and eyes shut’ attitude was the fountainhead for the confusion of responsibilities that permeated planning and execution. In a cruel twist of fate, Hall’s doubts became self-fulfilling prophesies, because he shunned his responsibilities.

But even if Hall’s assertion that the decision should be made by the man on the spot has merit, that would not justify delegating the decision as far down as eventually happened. At the British beaches, the decision was delegated only down to their equivalent of the Deputy Assault Group Commanders. Recall that Hall’s two Deputy Assault Group Commanders were naval captains (equivalent to Army colonels), both of whom would meet the DD/LCTs at Point K and escort them to the 6,000 yard line for deployment. In other words, they, too, would have been ‘on the spot’ if a decision needed to be made. That would have been the far better solution.

In addition, any validity to his rationale faded to nothing in light of two subsequent events. First was the landing at Utah Beach, where RADM Moon made the launch decision with MG Collins’ advice, and where the Deputy Assault Group commander was on the spot in the boat lanes to issue orders to adjust when the DD/LCTs arrived late. Second, the assumption that very junior officers with six weeks training on DD tanks were the best men to make the decision proved patently unwise. This was an especially risky option as their decision would determine the fate of a critical slice of combat power, upon which so much of the first waves’ success depended.

Hall’s judgement was seriously faulty.

But the question remains, was this truly the guidance Hall issued before the operation? It certainly was never reduced to writing in his own order, nor was it reflected in any of the Army orders. Was this merely Hall revising history to avoid accountability? MacLaughlin once again comes to our aid. His after action report stated Hall and Gerow came to an agreement that:

“ . . . the senior naval commander in each flotilla carrying DD tanks make the decision as to whether the DDs would be launched, or the LCTs beached and the tanks unloaded on the shore. The senior DD tank unit commander was to advise the flotilla commander in this matter.”[7]

While generally in line with Hall’s version, there was a significant difference. Where Hall described a joint decision, with the Army responsibility emphasized by being mentioned first, MacLaughlin’s version clearly indicated it was a Navy decision, with Army input (paralleling, in part, Bradley’s position). Thus, from this initial decision, the Navy and Army were not on the same page regarding this key responsibility. Such is usually the case when contentious matters are decided without being documented or translated into orders.

And apparently, not all the actors within the Navy were on the same page, either, and this failure was also a result of Hall’s faulty planning. Neither Hall’s original operation plan (dtd 23 May 1944) or its subsequent change (30 May 1944) mentioned such a decision would be a joint Army-Navy responsibility. His original order merely instructed two of his Assault Group commanders that the DD tanks might have to be landed, and left unstated who would decide. In the absence of guidance from above, the orders of the two assault groups were naturally disjointed. The Assault Group O-1 order did mention the decision would be a joint Navy-Army responsibility, but only mentioned it in a footnote to an annex detailing the employment of Landing Craf, Support (Small). The order for Assault Group O-2 didn’t address the topic at all. Further, by the time Hall’s order and the two assault group orders were issued, the DD/LCT teams had been broken up, with the LCTs and their embarked DD tanks already sailed for Portland, and the tankers already shipped off separately to the final marshalling areas. If either the Assault Group Commanders or their deputies had any additional role in clarifying or coordinating the matter (most critically with the sequestered tankers) it was not recorded.

The final act in this confusion occurred just a day or two prior to the initial sortie, when the tankers rejoined the LCTs in Portland Harbor. This was when Rockwell decided that instead of the decision being made separately within “each of the two LCT units carrying DD Tanks,” he would insist on one Army officer making the decision for both LCT units. Although he didn’t mention what role, if any, he would have in this proposed change, it was clear he was attempting to override both Hall’s agreement with the Gerow and the Assault Group O-1 order. Whatever Rockwell hoped to achieve, his actual result was to introduce more confusion. Barry, leading the DD/LCTs of Assault Group O-1, understood that the decision reached at that meeting placed the decision authority solely in the hand of the Army. Both his Army counterpart (CPT Thornton) and his own OiCs operated on D-Day consistent with that belief. For that matter, Rockwell’s oral history indicated he and Cpt Elder did as well.[8] All of this ran completely opposite to the version Rockwell penned after the landing.

Rockwell also had a hand in the cascading embarkation errors. While he was not solely responsible for the disconnect between the embarkation scheme and subsequent sailing instructions in Assault Group O-1, it’s clear he conducted embarkation with inadequate information. This was compounded by failing to anticipate how the changed sailing instructions would impact the placement of Barry within the formation he commanded. This then led to the last-minute switch between the OiCs of two LCTs, which in turn led to Barry and Thornton being physically separated (during a period of radio silence), and indirectly led to the new OiC in Thornton’s craft getting lost in the boat lanes. . . . which in turn, forced Thornton to make a decision while separated from three quarters of his command. Every error compounded the effects of the previous error and all conspired against sound decision-making in the DD/LCTs of Assault Group O-1.

Rockwell was more directly responsible for the error which saw Companies B and C of Assault Group O-2 being loaded on the wrong LCT sections. While this did not seem to affect the outcome within his own division on D-Day, it was another distraction that had to be managed as he was dealing with other problems just before the sortie.

Barry and Thornton do not escape responsibility, though it is abundantly clear their share of the blame is far, far less than Hall, Rockwell and history have heaped on them. Objectively, Thornton made the wrong decision. Were there mitigating considerations? Yes. Reports of the state of sea and wind varied widely among observers, and to make an Army officer responsible for a decision based on his judgement of sea state is simple folly. Yet he was stuck with that decision, and he made the wrong one. It appears to have been an honest mistake, but mistake it was. The bottom line, however, was that his error was just the last one of an unbroken series of errors that started with Assault Force Commander, and which could only result in disaster of one sort or another.

Barry’s responsibility is far more difficult to assess. He was largely a victim of Rockwell’s poor decisions regarding chain of command, formations and placement of Barry within that formation. As a result of Rockwell’s belated recognition of his own error, Barry set off on 5 June in an unfamiliar craft, with an unfamiliar crew, in charge of a formation three quarters of which were not from his normal flotilla, group or section. Worse, Barry’s understanding of the outcome of Rockwell’s agreement on who would make the decision to land would place him in the precise position – with no role in the decision – for which Hall would later excoriate him.

One other category of responsibility must be noted. This involves the two Deputy Assault Group Commanders (CAPT Imlay and CAPT Wright). Theirs are errors of omission, not commission. While they both noted how bad the sea conditions were, neither took the initiative to intervene. It’s hard to put all the blame on a junior officer’s decision, when older, wiser heads with more braid on their visors stood by and failed to act. The blame here is somewhat worse for CAPT Wright, who, instead of leading the DD/LCTs to the 6,000 yard line, had CAPT Sabin take that role while he went back to the Transport Area to tend to his LSTs.

Also falling into this category are various Army officers. MacLaughlin was involved from the outset in the contentious matter of who would make the decision, and while he clearly knew how important it was, he failed to monitor the developing plans and ad hoc decisions – at least there is no record of him objecting as the process continually went awry. He can be partially excused as he apparently was aboard the USS Ancon and not present when Rockwell held his pre-sortie meeting with the Army battalion commanders. Assessing the role of the two tank battalion commanders is difficult without knowing how much of the internal Navy confusion they were aware of, whether they were aware of Bradley’s position or whether they knew of Hall’s agreement with Gerow. The tank battalions’ own orders had been issued before those of the two naval Assault Groups—which, in any case these units may not have received—so could not incorporate any of the (sparse) guidance the naval orders included. Beyond that, without a reliable, independent source for what took place in Rockwell’s pre-sortie meeting, there is no way to know whether their role in that meeting was constructive or added to the confusion. The only judgement that can be rendered here is a very general observation that they did not impart a strong enough sense of caution on their company commanders. Even this limited observation really only applies to LTC Skaggs of the 741st Tanks Battalion and is tempered by the fact that Skaggs’ version of events has never been put on the record (despite his offer to provide it to Cornelius Ryan).

And of course, the Army chain of command—from the 16th Regimental Combat Team through the 1st Infantry Division to the Vth Corps—can be similarly faulted for not paying enough attention to this critical matter. As early as December 1943, Gerow voiced his doubts at a conference on Overlord:

“I don’t know whether it has been demonstrated or not: what will happen to those DD tanks with a three- or four knot current? . . . I question our capability of getting them in with that current and navigation.”[9]

Having such doubts so early in the process, one can fault Gerow (and probably others) for failing to watch more closely the evolving plans for employing the DD tanks. These were errors of omission, but did fall directly within a commander’s explicit responsibility for supervision.

The most unconscionable part of this tragedy took place in the days, weeks and even months after 6 June, when individuals were seeking to avoid blame. Rockwell’s actions come in for the most severe criticism, if for no other reason than short-stopping the reports of the LCT OiCs. He misrepresented the comments of the OiCs to the benefit of his version of events. Worse, he wrote his own action report before he even received two of the OiC reports, one notably being Barry’s. That meant Rockwell condemned Barry without even considering his account. And the fact that Barry’s account directly contradicted Rockwell on the most vital point casts Rockwell in an even worse light, from which one might logically infer he did that intentionally to keep the potentially embarrassing facts of the matter buried.

Rockwell’s hypocrisy was further emphasized with his decades-later admission that within his own division, they had indeed launched “one or two” DD tanks that promptly sank. This revealed that Rockwell’s judgement was also so poor that he allowed launching in ‘clearly unsuitable’ weather conditions – the same sin for which he condemned his scapegoat, Barry. Again, it is another vital point he seems to have concealed when the hunt for someone to blame was under full swing.

Hall’s endorsement of Rockwell’s report (quoted in part above) was equally as self-serving, and, if not blatantly false in parts, was at the very least ill-informed. Any agreement he may have reached with the V Corps Commander had long since been rendered outdated by sloppy orders or the unsanctioned changes Rockwell instigated just before sortieing. Had Hall been kept in the dark on this? Clearly not, as Rockwell’s report plainly stated the decision had been left to the senior Army officer of each group. Which indicates Hall was trying to spin the facts.

Hall’s endorsement omitted the point that Elder had launched ‘one or two’ tanks without consulting Rockwell (as Rockwell noted in his oral history), which would have revealed that Hall’s joint decision policy had been disobeyed. This is likely because Rockwell concealed that matter from Hall (and from history for 40 years), just as he had withheld Barry’s report. But if Hall had been kept in the dark on this point, it demonstrates the fact that Hall’s inquiry into the matter had been woefully inadequate. So, was Hall uninformed of this? Or did he know and simply chose to omit it? This is crucial, as up to that point, the Rockwell/Elder team had functioned exactly as the Barry/Thornton team had, the only difference being Rockwell/Elder took action to stop the mistake before it became total. This distinction was lost on Hall, and as a result his endorsement drew a comparative picture that was false and prejudicial to Barry and Thornton.

And finally, Hall’s bland assertion that the Army and Navy leaders were supposed to consult by radio is undermined by his order that did not grant them authority to break radio silence. Rockwell’s oral history made it clear that when Elder and he broke radio silence, it was in violation of orders. (Although the tank radio nets were authorized to be opened at 0500 hours Rockwell’s report and oral history both indicate he was not aware of that, and there is no indication Hall was, either.) Again, Hall’s endorsement painted a picture that was not an accurate reflection of the operational conditions Hall himself had set.